The railway, like the elevator, or like (in its recreational form) the Ferris wheel, puts stilled bodies in motion. What these mobile technologies make possible, in different forms, are the thrill and panic of agency at once extended and suspended*.

—Mark Seltzer

SUNFLY

The modern day lyric video is a bricolage of emotive cues, graphics, and text, taking us beyond the frame as we typically understand it. A diagram of psychodynamic prompts, it is a media mechanism with its own relationship to immersion, motion, and cinematographic illusionism.

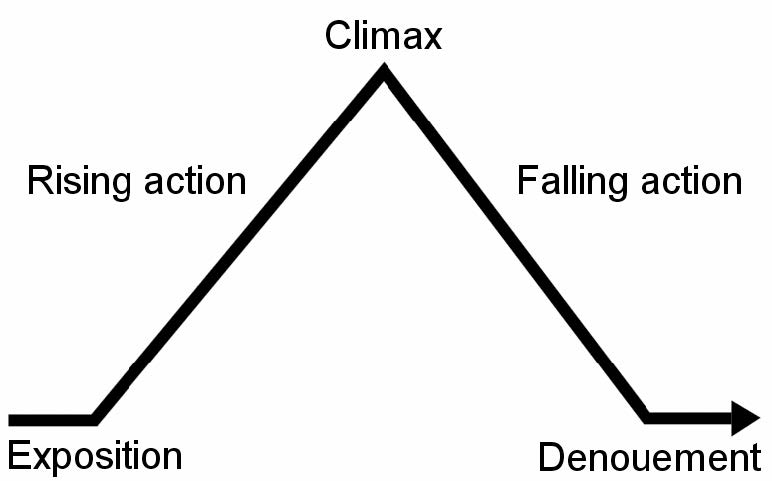

As a conduit between intimacy and homogeneity, the modern day lyric video produces a new kind of technological kinship. It has become yet another cultural expression in the realm of “thrill and panic of agency at once extended and suspended”, but it has done so on the register of illustration: emotions rev up and down to the beat of the sonic ear worm, following, more or less, the time and tension of narrative plot structure.

The lyric video also exemplifies the tension between the gaze of a body outside screen space and the flat matte screen reflected back. Because lyric videos rarely invoke narrativistic style and live-action cinematography, the way a typical music video would, a viewer’s gaze falls flat, literally. Opposite of stereoscopy, the lack of topographical depth makes the highlighted text feel like a well-worn phrase or idiom. Like an entropic and automated e-book, the pages turn without our input.

The screen is a memory device, a mnemotechnic which burns the verbiage into you at the same time as it reflects mere sensibilities and affective cues. The scripted sensations are rarely encapsulated or described by bodies in screen space, but rather, by the kinetic typography and vivid backgrounds which extrude and fulfill them.

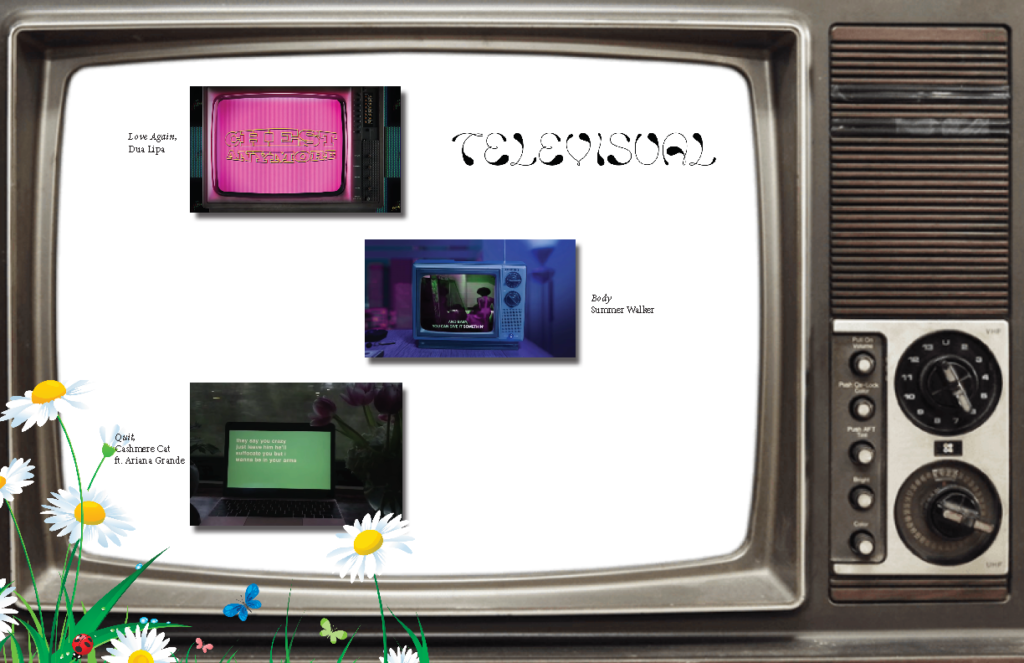

The tension between the embodied experience of watching and the flatness of graphic space is tropified into a lyric video subgenre with a stubborn persistence: televisuality. Lyrics appear on television screens that exist in the diegetic world of the video, pointed back out for the viewer to consume. Except, of course, that the screen is pointed at the imaginary ‘lens’ of the digital software doing the compositing—as often, these videos are directed start-to-finish in visual editing software. The endless loop of televisual reflection makes the lyric video into its own audience member.

Quit by Cashmere Cat ft. Ariana Grande is a contemporary stylization of the picturesque as told through televisuality. A laptop rests on the lower lip of a window of a train car, animating lyrics in hyper-neon fullscreen. The handheld camera’s “gaze” is directed at the laptop, framed by bouquets of flowers and potted plants. When the song teeters off the edge of its pre-chorus, where the vocals momentarily stop, our gaze is directed wistfully to the spatial montage outside the window. The fast-moving forests and powerlines compress the song’s sentiments of regret and longing into a chain of signifiers. The infrastructure mosaic is both the inside and outside of train space, however—as much the potted plants as the dominion of the “real” nature, messy and unkempt, outside the frame. The lyric video relies on the assumed transmission of landscape as a record of the “everyday”, made exceptional and symbolic when a viewer is grief stricken. One feels the productivity of being transported somewhere, of treading significant territory—physical and emotional—despite being technically motionless. Nature becomes a monument to melancholy, a pop-music casualty of its status as both generic and spectacular at once.

Put differently: the harmony of nature and machine is made into a still life. The transport of still persons across landscapes converts landscapes into the unrooted, arrested nature of the still life. The shifting gaze of the camera, in this case, reduces the entire scene to a televisual still life, buffeted by the symbolic register of the floral arrangements. Seventeenth century Dutch still life paintings brought together assemblages of flowers that could not possibly bloom at the same time, becoming early progenitors of the deceptive/strategic logic of media to impart its symbolic and emotive registers. Lilies stood for purity, sunflowers meant faith, tulips became stand-ins for nobility. Together, the impossible bricolage became sobering examples of memento mori, or effective portrayals of vanitas. Like the memento mori of a love once consummated onboard.

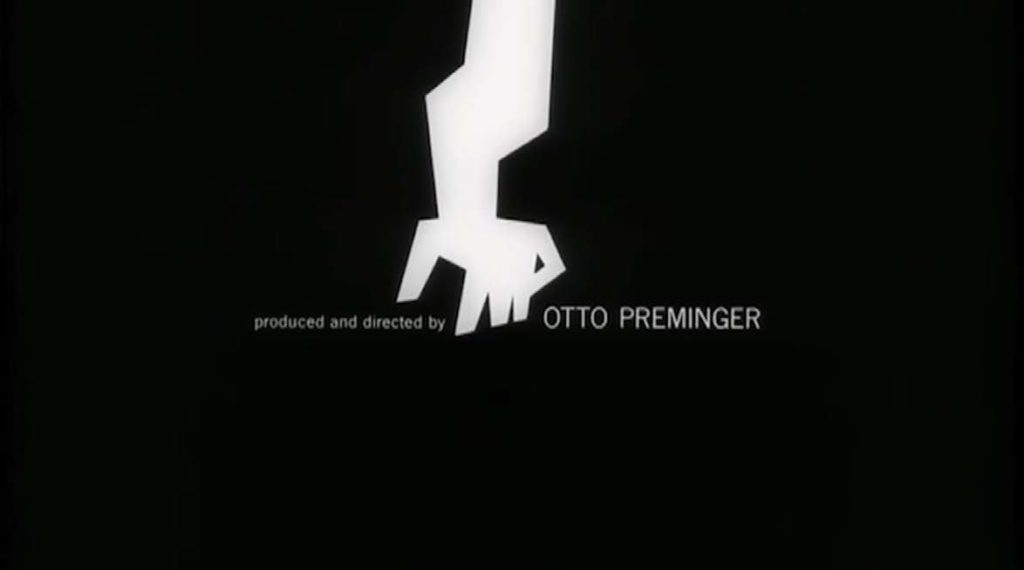

The lyric video has some obvious precedents. Kinetic typography, which combines animation with ideas a text conveys (“up” = text floats upward), is one such precedent, as is the pioneering work of designer Saul Bass. His cinematic title sequences worked towards an accurate synthesis of a movie’s ad campaign into theaters, as well as towards the creation of an emotional climate for the story to come.

jarring and disjointed existence of a drug addict.

Still, the crystallization of dynamically moving text and image into the lyric video follows a long image regime in which the sort of qualification of images by/with text increasingly becomes the main way in which we see images. An image often comes with the anticipatory thrall of its accompanying text block. Images are thus punctuated by comments about them, regardless of whether one immediately sees them (or ever does). The commentary can be felt, like a form of rhythm introduced into a visual paradigm.

Breaking time into a series of disjointed yet flowing parts, lyric videos layer captions with emotions that are only meant to last as long as words are spoken. They belong to a wholly other category of expressionism, warping meaning into bit-sized psychic spaces. One part transitional object, one part broken-montage, the lyric video is a project of refiguring the relation between flat, graphic space (“caption”) with its milieu, or else a case study of the moment-to-moment manipulation of ideology.

- *Mark Seltzer, Bodies and Machines, New York: Routledge, 2016.