A layered body. This is an aching archive – the one that contains all of our growing grief, all of our dispossessed longing for the bodies that were once among us and have gone over to the side that we will go to too. When I told you that I will probably haunt you, you made it about you, but it is about me. The opposite of dispossession is not possession. It is not accumulation. It is unforgetting. It is mattering.

Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective*

For those to whom history has not been friendly, for those who have known the cruelties of political becoming, those who demand in the shadows of dying technologies, those who live in the sufferings of defiance, those who live among the abandoned aspirations which were the metropolis, let them bear witness to the ideals which in time will be born in hope. In time let them bear witness to the process by which the living transforms the dead into partners in struggle.

John Akomfrah, Handsworth Songs, 1986

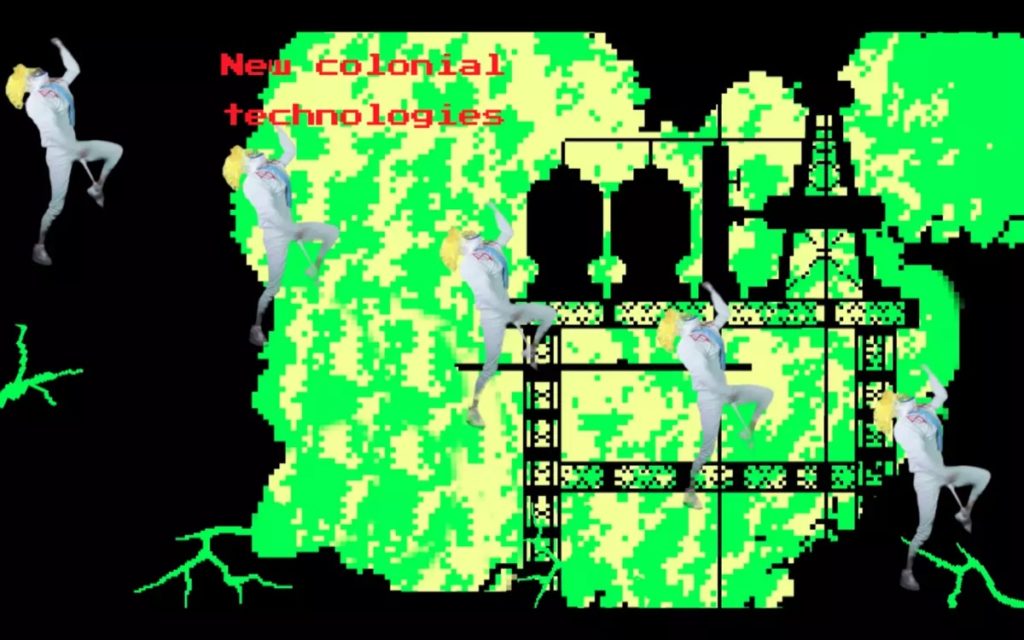

Constellating time periods, organisms, cosmologies, and environments ranging from pixelated video game-like scenes of dispossession to underground caves of clay, Naomi Rincón Gallardo’s The Formaldehyde Trip (2017) is a palimpsestic journey through History that activates the undead as a state of radical possibility and healing. Weaving together songs, video, performance, and fabulation, the work takes two forms –appearing either as a performance accompanied by live music and a projected screening of the work’s video component, or as a nine-channel video installation.† The piece follows apparitions of the axolotl, a salamander-like ancient native of Mexico, and a fabulated journey of Alberta “Bety” Cariño, a Mixtec activist who was murdered in 2010. Through these incarnations, The Formaldehyde Trip plants seeds of resistance. The work crosses from the living realm to the underworld and back again, materializing Mesoamerican cosmologies, indigenous women’s struggles against dispossession, and the powerful potentials of collective memory, touch, and movement. Psychedelically transtemporal, The Formaldehyde Trip embodies the undead, infusing this avatar-like state with the potential for sprouting “rage, dignity, and care together with concrete and utopian possibilities.”‡

In both versions of The Formaldehyde Trip’s presentation, the figure of the axolotl initiates the viewer’s own trip through various states of being and temporalities. The Formaldehyde Trip begins with the axolotl in suspension. When performed live, Gallardo becomes this creature, walking out on stage dressed in an amphibian headdress and jumpsuit, freezing as though encased in a tube of formaldehyde solution in a museum.§ The video component of The Formaldehyde Trip also begins with shots of Gallardo as axolotl, kicking and twisting underwater, at times appearing as though attempting to drown.

Explicitly stating their own undead and transient nature, Gallardo as axolotl offers a poignant avatar and entry point to The Formaldehyde Trip’s engagement with temporality, dispossession, and colonization. For centuries, axolotls have resisted evolutionary metamorphosis. They retain their larval features through adult life, are fully capable of reproducing in a larval stage, and can regrow their limbs and organs. Gallardo has noted in their own writing on The Formaldehyde Trip how the axolotl’s neoteny has historically been a source for necrophilic study, categorization, and attempts at preservation. The second chapter or verse of The Formaldehyde Trip highlights this highly fetishistic interest. This sequence features the “discoverer of the axolotl,” Alexander von Humboldt. Dressed in drag, Humboldt sings with erotic vigor his desire to possess, classify and conserve the body of the axolotl.

The Formaldehyde Trip proposes, however, that the axolotl’s neoteny is also a strategy of resistance. The axolotl is timeless in its evolutionary trajectory. Its neoteny refuses a binary logic hierarchizing advancement over delay, sophistication over crudeness. The axolotl has survived and regenerated in its neotenous form despite the violent ecological, biological, and social upheavals of colonization. Gallardo’s piece does not consider this kind of biological suspension as a foreclosure. The Formaldehyde Trip incorporates it as part of the axolotl’s own power as an avatar, asking what might happen when suspension in time and space, resulting from neoteny or death, shifts into a form of awakening and regeneration. The possibilities of this question are actualized in one of the final scenes of Gallardo’s video, where a large axolotl sculpture positioned atop vines and flowers oversees a healing capsule on the lake of Xochimilco. The capsule draws its healing powers from the axolotl’s abilities torestoretheir limbs and reproduce despite their “undeveloped” biological trajectory. The undead, timeless axolotl is evoked as a powerful avatar that can unravel a linear trajectory of History by slipping between real and fabulated realms as well as through past, present, and future temporalities.¶

In The Formaldehyde Trip, a use of fabulation and the presence of avatar figures representing Bety Cariño, her companions, and the axolotl, offer an alternative to a frozen, stoic recording of history. Fabulation has a complex history in literature, theater, cinema, and art. Across these media, however, the term consistently “refers to the sequence of events that form the invariant core of a narrative, the ‘what happened.”# Although fabulation is linked to a certain fabrication, critical applications of the practice expand the fabulists’ position from being a mere liar. Rather, an engagement with fabulation –an active participation in re-rendering elements of a narrative or history– exposes relations between “the truth” and its inherent gaps. Saidiya Hartman famously coined the term “critical fabulation” in her essay “Venus in Two Acts,” a text which thinks through the chasms and violences that are deeply rooted in many representations of enslaved people and their histories. Hartman articulates how fabulation can be deployed as a strategy to underwrite dominant narratives that have historically systematically marginalized and obscured certain voices, showing how “by playing with and rearranging the basic elements of the story, by representing the sequence of events in divergent stories and from contested points of view,” one is able to “jeopardize the status of the event, to displace the received or authorized account, and to imagine what might have been said or done.”**

Hartman’s infusion of fabulation with a critical edge has led to further examinations of fabulation’s potentials, particularly in the realms of art and performance. For instance, we can look to the practices of artists who use fabulation as a means to operate and intervene within the dynamics of our information-laden and “post-truth” era such as Walid Raad, Adrian Piper, and Cheryl Dunye.†† Importantly, fabulation is not deployed by these artists to elicit a “gotcha” moment where the viewer realizes that they have “been had,” or fooled by the artist. Instead, fabulation allows for immersion in a liminal and multitemporal zone. This zone decenters a singular authoritative recounting of events, allowing space to acknowledge that invocations of History often denote implicit forms of exclusion. Fabulation turns to the potentials of reimagination and reincarnation as a form of generative resistance to the History which has consistently erased the voices, lives, ontologies, and cosmologies of non-white-male-heterosexual bodies and communities. Yet, fabulation does not seek to establish a new truth that entirely reconciles these violences and injustices. Applied critically, fabulation insists upon the irreversibility of holes, gaps, and chasms. It is “a doing of history that is a showing of the doing of history, and in that showing, history’s undoing.”‡‡

Avatars find a natural home within The Formaldehyde Trip’s palimpsestic fabulation. An avatar is an incarnation, embodiment, or manifestation, an entity that exists and slips between the real and the virtual. Each of the characters followed in The Formaldehyde Trip can be considered an avatar,from the undead and evolutionarily timeless axolotl, to the figure of Bety metamorphosed as Coyolxauhqui the Mexica moon goddess, as well as her companions/guides through death and healing. These are beings that span various temporalities and each one enacts a form of resistant manifestation via their reincarnation in Gallardo’s piece.

The definition of an avatar also has a complex history. In Sanskrit, an avatar is an earthly incarnation or emanation of a deity, literally translating to “downcoming.”§§ Since the 20th century, the term has acquired a much more banal and technologically linked meaning –specifically being used to denote a graphic icon or figure that is controlled by and represents a person in a digital context.¶¶ The avatars in The Formaldehyde Trip manifest both in digital and mystical contexts, as people, actors, and as computer-generated icons. Furthermore, the avatars in Gallardo’s work are mobile entities. Bety’s avatar, her companions, and the axolotl journey from death to healing, re-cording History and shifting between physical manifestations, temporalities, and locales. ##As David Joselit notes, an avatar’s spatial journeying is one of its key characteristics. According to Joeselit, the avatar is “more the index of a location than a traditional form of subjectivity, an avatar does not possess an identity but rather exercises one (or many) provisionally in order to chart a particular path. As a fictional character controlled by an actual body, it is defined by where it goes rather than what it is.”***

Furthermore, as Uri McMillan has articulated, “avatars act as extensions of our agency, while also revealing a persistent slippage between real and virtual worlds…Avatars, in short, act as mediums – between the spiritual and earthly as well as the abstract and the real – and the uses of those mediums, as well as their attendant meanings, continue to morph.”††† The Formaldehyde Trip’s avatars inhabit contexts outside of a distinct temporality, appearing as the floating/frozen axolotl in the first scene of the film, within the digital sphere of accumulation and dispossession that resembles a pixelated Minecraft scene in another instance, and in a gravity-less cosmos where Bety and her companions float, dance, chant, and assert their germinating seeds of resistance in the final moments of the video. The Formaldehyde Trip’s avatars also occupy filmed scenes in the “real world,” practicing self-defense movements amidst a rural landscape, slathering mud, making tortillas in a smoky hut, and floating on the lake of Xochimilco. Across these scenes the avatars are transient, existing in an indeterminate and relational zone where, like in the space of fabulation, time is neither defined nor beholden to a linear structure. In this zone of transience, the boundaries between the spiritual and the earthly are collapsed. Gallardo’s imagination or representation of these figures is not burdened by biological, historical, social, and hegemonic constraints. The avatars are “undead but not living,” a state which ultimately allows “travel across historical and contemporary colonial patriarchal structures imposed upon land, women, and Indigenous peoples of the Americas.”‡‡‡

The undead avatar as a state of transtemporal existence offers a potent site for Gallardo’s speculative germination of Bety Cariño’s ghost and its apparitions in collective female, queer, and indigenous circles. Bety dedicated her life to opposing extraction projects threatening not only the land, air, and water of Indigenous communities, but also their worldviews and ways of life. On April 27th, 2010, Bety was murdered in a paramilitary ambush along with Jyri Jaakola while on a humanitarian caravan to San Juan Copala, Oaxaca. The Formaldehyde Trip memorializes the murder of Bety Cariño using a language of expansive collectivity, creating a narrative that begins from the moment of Bety’s death, traverses through the underworld, and metamorphoses through a collective ritual of Bety’s resurrection as Coyolxauhqui, the Mexica goddess of the moon. In Bety’s journey through the underworld, she finds companions in witches, widows, animals, and Mesoamerican deities. These fabulated avatars wear DIY armor made from plastic jugs and sheets painted bright pink, hold giant dildos with axolotl tips, and take on features that at times are monster-like or evocative warriors from a sci-fi movie. Bety’s companions participate in self-defense choreography in one scene of the video, arming themselves against threatening forces of neoliberal dispossession, which as Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective write in “Before Dis-possession, or Surviving It,” is not only a matter of land expropriation, but also a determination of precariousness, a process which delimits whose bodies should be shielded, and whose are of lesser importance and can be wasted.§§§ The Formaldehyde Trip’s avatars and the work’s fabulation of Bety’s death/manifestation in an undead state, are a way to subvert this precariousness, drawing together bodies and infusing them with the power of creation through assembly and collectivity.

Bety’s fabulated avatar companions are practitioners of care. In one scene, widows clean Bety’s body, cook mole, flatten tortillas, and prepare her body for a transition to the underworld. In a followingsequence taking place in the muddy cave of the underworld several eclectically soldered together queer, non-human, Mesoamerican deities receive Bety’s seed. Gyrating to punk music as they slather a hip of clay in the middle of their circle, these avatar deities participate in a kind of collective molding process which actively receives and regenerates Bety’s seed through touch and kneading. The axolotl speaks to a sense of collectivity at the outset of this sequence, narrating that “according to the Mesoamerican worldviews, the underworld is a cold and dark but nonetheless lush place where dead bodies blend together in a nourishing clay made out of bones and ashes…Dead people lose their individuality while their hearts become seeds underneath the earth. The underworld is described as a warehouse of a great variety of materials: seeds of hearts, animals, and flora of every kind, and all the substances that form the cosmos.” In the mud cave, the tactile generative potential of clay, pleasure, and bodily togetherness, is heightened by the pulsating rhythm and the chorus of the figures who say in unison, “mud, mud, mud / stubborn and reluctant / mud, mud, mud / the tomb does not stop us / mud, mud, mud / we are not tired / mud, mud, mud / nor discouraged / mud, mud, mud / again and again dead / mud, mud, mud / forever indomitable / mud, mud, mud / illegible monsters / mud, mud, mud / Coyolxauhqui imperative.”

The Formaldehyde Trip’s use of avatars also underscores that Bety’s death is not an isolated tragedy. Her murder is a repetition of both past and present atrocities that have been committed by the hetero-patriarchal state. In Mexico and beyond, the state has been complicit with transnational capitalist endeavors and sponsored paramilitary groups in mobilizing against Indigenous women defending their land, way of life, and means of survival.¶¶¶ The deaths of these women are symptomatic of the state’s fear of their collective episteme and their resistance to transnational capitalist agendas.### The Formaldehyde Trip invokes this same collective episteme through its avatars. By definition, avatars are not necessarily representative of a discrete person and can be understood as a broader constellation of entities or thoughts. Additionally, the work never presents a scene of an isolated female figure. Bety’s descent into the underworld is accompanied by the chant, “I am not one no-no / I am many at once,” and then goes on to say “I am not one no-no / I am Bety, Bertha, Tere, / Felicitas, Fidelia, / Esther, Irma, Selena / I am not one no-no / I am Néstora, Ramona, / I am Trini, Miriam, Kelly, / Everilda, Florencia.” Here, the expansive potential of Bety’s undead state is further activated through her being’s fabulation in The Formaldehyde Trip. Bety becomes a reimagined figure who has embodied elements of other women’s lives and stories. Her avatar is one who holds space for and articulates narratives that have been suppressed and forgotten but that deeply matter despite their elision from linear, heteropatriarchal Histories.

In the final scene of The Formaldehyde Trip, fragmented pieces of Bety float in a digitized, twinkling cosmos. Companions, warriors, and other creatures from the underworld dance around her. Compositing energy, these figures pulsate with sound, swing axolotl dildos, and rehearse the self-defense moves in their creation of a new resurrected body for Bety. The figures create a circle around the digitally floating figure of Bety, whose posture is in mid-stride. Her regenerated body is formed and framed by a collective web, echoing The Formaldehyde Trip’s overarching emphasis on the power of collectivity and the fact that Bety’s story is not a singular tragedy, but part of an ongoing attack on indigenous cosmologies, lands, women, and ways of life. Yet, The Formaldehyde Trip does not become paralyzed as a narrative of pain. The work turns to forms of creation, utilizing fabulation and reincarnated avatars to ultimately enact an active chronicle of care. As Gallardo writes, “Bety Cariño’s ghost will keep returning in different apparitions because her duty was brutally interrupted. And when her ghost visits, we will welcome her with other futures harvested from her legacy. Or we may meet her in the underworld, to join the great reserve of dignified seeds, germinating to sprout a burning revelation destroying the world as we know it, for the emergence of a flourishing planet.”**** The final verses of The Formaldehyde Trip cry out a mantra invoking this avowal. At first, a voice wails “how do you cope?” The next verse asserts in a chorus, “learn to see/ From the cracks / Talk back /Write back / Take back energy/ Flourishing planet/ Ecologies of caring / Inter-knowledge/ Scavengers of subjugated knowledge.”†††† Death is not an end. Mourning, while being a conduit for closure, is also an expansive practice which gathers bodies together in solidarity. The ground is sown for generative healing through initiating and conceiving modes of re-emergence, pleasure, and affirmation that sprout through the cracks and remain.

- *~Angie Morrill, Eve Tuck, and the Super Futures Haunt Qollective, “Before Dis-possession, or Surviving It,” _Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies 12_, no. 1 (2016): 2.

- †~_The Formaldehyde Trip_ was originally commissioned as a live cinema concert by SFMOMA as a part of _Performance in Progress_ and was co-curated by SFMOMA and Galería de la Raza.

- ‡~Naomi Rincón Gallardo, “The Formaldehyde Trip: A Mythical/Critical (Under)World-Making Dedicated to Bety Cariño,” _Critical Ethnic Studies_ 4, no. 2, (2018): 67.

- §~Gallardo as axolotl narrates the performance and video sequence when the work is performed live, “through an exercise of therianthropy, I perform the abilities of a _nahual_, a figure that changes from human to animal form.” Ibid., 41.

- ¶Ibid., 40-41.

- #~Tavia Nyong’o, _Afro-Fabulations: The Queer Drama of Black Life_, Vol. 14, (NYU Press: 2019), 13.

- **~Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” _Small Axe_ 12, no. 2 (2008): 11.

- ††~Including Nyongo’s _Afro-Fabulation_. See also Lambert-Beatty, Carrie, “Make-Believe : Parafiction and Plausibility,” _October_ 129 (2009): 51–84; Michael Nash, _Experiments with Truth: The Documentary Turn_, (Philadelphia: FWM, The Fabric Workshop and Museum, 2004); Okwui Enwezor, “Documentary/Verite: The Figure of ‘Truth’ in Contemporary Art,” in _Experiments with Truth: The Documentary Turn_; Mark Nash, “Reality in the Age of Aesthetics,” Frieze 114 (April 2008); Mark Godfrey “The Artist as Historian,” _October_ 120 (Spring 2007): 140-172; Nato Thompson, “Strategic Visuality: A Project by Four Artist/Researchers.” _Art Journal_ 63, no. 1 (2004): 38-40; Fred Moten, _In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition_, (University of Minnesota Press: 2003).

- ‡‡~Nyong’o, _Afro-Fabulation_, 23.

- §§~Uri McMillan, _Embodied Avatars: Genealogies of Black Feminist Art and Performance_, (NYU Press: 2015), 11.

- ¶¶Ibid.

- ##This element is further extended in the live performance of the work, which adds another layer of temporality with the presence of an audience and performers.

- ***~David Joselit, “Navigating the New Territory: Art, Avatars, and the Contemporary Mediascape,” _Artforum_ 43, no. 10 (Summer 2007): 276.

- †††~McMillan, _Embodied Avatars_, 11.

- ‡‡‡Gallardo, “The Formaldehyde Trip,” 41.

- §§§Morrill, Tuck, Super Futures Haunt Qollective, “Before Dis-possession, or Surviving It,” 7.

- ¶¶¶~See Isabel Altamirano-Jiménez, “Indigenous women refusing the violence of resource extraction in Oaxaca,” _AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 17_ (2), (2021): 215–223.; Mishuana R. Goeman, “Ongoing storms and struggles: Gendered violence and resource extraction,” in Joanne Barker (Ed.), _Critically sovereign_, (Duke University Press: 2016): 92–126; Friends of the Earth, “Resisting the Growing Power of Transnational Corporations in Latin America and the Caribbean: Compilation and Summary of National Assessments,” December 2021. Accessed June 17, 2023, [https://www.foei.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Resisting-the-growing-power-of-transnational-corporations-in-Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean.pdf](https://www.foei.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Resisting-the-growing-power-of-transnational-corporations-in-Latin-America-and-the-Caribbean.pdf).

- ###Gallardo, “The Formaldehyde Trip,” 68.

- ****Ibid.

- ††††Ibid., 69.