Collective Mesh

Objects have shaped social constructs and promoted the evolution of the human in an extended amount of decades, while modern technology has done so in only a few. Indeed, over the last century, sensorial inputs such as hearing, sight and touch have found themselves submerged by the exponentially increasing fluxes of external stimuli induced by the ever growing presence of new technologies in our lives. The inevitable exposure to technology and hyper-mediation has considerably influenced our conception of time and space resulting in drastic behavioral and psychological changes. Reality shifts from one side of the interface to the other, gradually blurring the line between realities and virtualities as is the case with VR and symptoms of derealization—the feeling by which reality crumbles, a reaction to the sudden illusory surroundings, a perceptive glitch*. Processes of translation from analog to digital information are inherent in every computer, phone or tablet. Yet the opposite procedure (a translation from digital to analog through our biological receivers) has left its traces along the way, traces that can be referred to as techno-rituals. In parallel to a fast developing techno-scape, humans have unawarely adopted some of the consequences as daily behavioral rituals. Techno-rituals include for example grids. Whether they are man-made external structures or an expression of our subconscious way of processing information, grids are an omnipresent layer to human perception. Indeed, they provide a way to simplify vision, interpretation and space. Moreover, the constant transformation of a continuous analog wave of information into a square digital signal (and vice versa) is a repetitive action that we find ourselves enacting over and over again. ‘Square-thinking’ becomes a repetitive habit, thus somehow an embedded ritual of human nature. Acceleration, another techno-ritual, is the result of the halting discontinuity of the computerized (digital) weaving in and out of the continuous elapsed moment (analog). In this scenario, a set of simultaneous actions such as hurrying, multi-tasking or taking food ‘to-go’ unconsciously worship data as bodies and minds try to imitate the behavior of a computer, scanning a substantial amount of information in the most productive way. On a more musical note, electronic music rises from data-craving spirits as a reaction to electric saturation. Techno music –as in music inspired by or created with digital processes– is a ritual that with a series of electronic sounds leads to a techno-driven spirituality through a sensory overload. Considering the DJ as a shaman, people are induced into a perceptional vortex through music that creates a deeper connection to the machine. The way technology acts upon us is so that it transforms behaviors and interactions, language and sensitivity, processes of reception and transmission… As part of an ongoing mutating process, the techno-human tries to find new sensations by testing the limit of its organic sensors. The following paper is a reflexion on the influence of modern technological devices on our bodies and psyche. It contemplates the mutation of a human possessed and consumed by technology, that forces its organic qualities to alternate between continuity and discontinuity, to embody several identities, several spaces, and several timelines. The first part expands on the fragmentation, multiplication and distortion of identities through the medium of Internet. The second part engages with the concept of ‘web 2.self’ that exposes a narcissistic web fed by its users’ self-adoration and exerting a vile mechanism of control through their ego. Finally, the third part speculates on a collective mega-structure as part of a final mutation between the organic and the wild web.

Mutation

Distortion Of The Self

Machines, acceleration, interfaces, microchips, networks, data centers… all these abstractions and non-abstractions converge into the ever-lasting, ever-growing, ever-parallel world generated by the Internet. It is the universal meeting point of mutual understanding between components and organisms that wouldn’t otherwise be able to communicate. It is a space where language, under certain circumstances, can be reduced to a minimal form that bypasses small distinctions in formats, creating a communal, universal, fractal tongue. The Internet along with our assisting technologies, generate a constant mutation of the values and principles that constitute the fundamental form of our social and cultural sphere, transgressing morality, ethics, politics, unicity, flesh and perception. The invention of television started a perceptual transformation in which the extensive proliferation of images would become an overwhelming means to achieve manipulated goals. Political propaganda, journalism, advertising and capitalist methods to establish a consumerist philosophy of obsolescence used extreme visual culture as a way to shape crowds and social imaginaries, triggering reactions such as McLuhan’s prophetization of media culture or Bourdieu’s discontentment of television. From that moment onwards, images become the primary source of reference and distribution of information. The Web and its extensive process of remediation of images produces a continuous current of fragmentation and reconstruction of the image, therefore of our understanding of it when filtered by our organic receptors. The repeated fragmentation of the information we are exposed to affects extensively the way we see and understand ourselves internally, creating also a fragmentation of our constitutive core, of our individuality, of our personality. James Bridle writes in one of his articles entitled “Living Inside the Machine” about the way we have created external structures that permeate into our internal structure. Computers and humans are not two different worlds anymore, they constitute one hybrid system that is still learning how to cohabit with itself. This hybrid dimension induces a distortion in material and psychic spaces, transforming the self into the selves, multiplying identities and reflections of a personality. Bridle says that “the ‘abstract machine’ is Deleuze and Guattari’s term for the sum of all machines – in their terminology, this includes the body, society, language, interpretation: like the rhizome it stands both for the sum and its parts. So the network too is one of these abstract machines: a mainframe, a terminal, a laptop, a wireless LAN, a string of satellites. And us too, living inside the machine, a part of the network.”† We are ourselves a machine, living inside another –abstract– machine, created by our own selves to our own image as defended by M. McLuhan when talking of media as an extension of ourselves and computers being designed like brains. The intricacy of these systems reflecting one another creates a feedback loop that carries away our personal, individual image, becoming itself its own feedback loop of endless reflections of identities shifting between reality and virtuality. Virtual Reality, even though existing in mechanical forms since the 50s, and used for medical or training simulations in the 70s, was commercialized for computer use in the early 90s. Despite having to wait more than twenty years to have its breakthrough, it offered another dimension, a parallel universe to explore, share and dream. Immersive in its idea, its execution is still bounded to reality by the weight and stiffness of its gear. Still, it is a promise of transcended worlds and imaginaries becoming real. In “TechGnosis”, Erik Davis explores the medium in the chapter The Alien Call, where he says that “VR is not simply a technology; it is a concept that exceeds mere gadgetry and all its inevitable bugs and breakdowns. The concept is absolute simulation: a medium so powerful that it transcends mediation, building worlds that can stand on their own two feet.”‡ The power of VR resides in its ability to create inhabitable simulations with the same feel that reality possesses. By doing so, it creates an alternative space for the mind while the presence of the body remains heavily in the gravitational space of Earth, therefore multiplying and expanding the fluxes of perception. Alternatively to VR, Multi-User Dungeons (MUDs) offered a virtual space cohabited by different anonymous users, where the identity carried after one’s birth, independent of one’s own choice, could be revoked, sculpted, edited, deleted, restarted and collaged to a preferred image of oneself than the one reflected by a mirror. MUDs have been studied extensively by Sherry Turkle through a psychological and anthropological standpoint and by Lisa Nakamura through the embodiment of identity tourism in online platforms. Identity in its singular form bears no more meaning. A person can be defined, non-pathologically, by a series of controlled, conscious personalities that can be performed online.

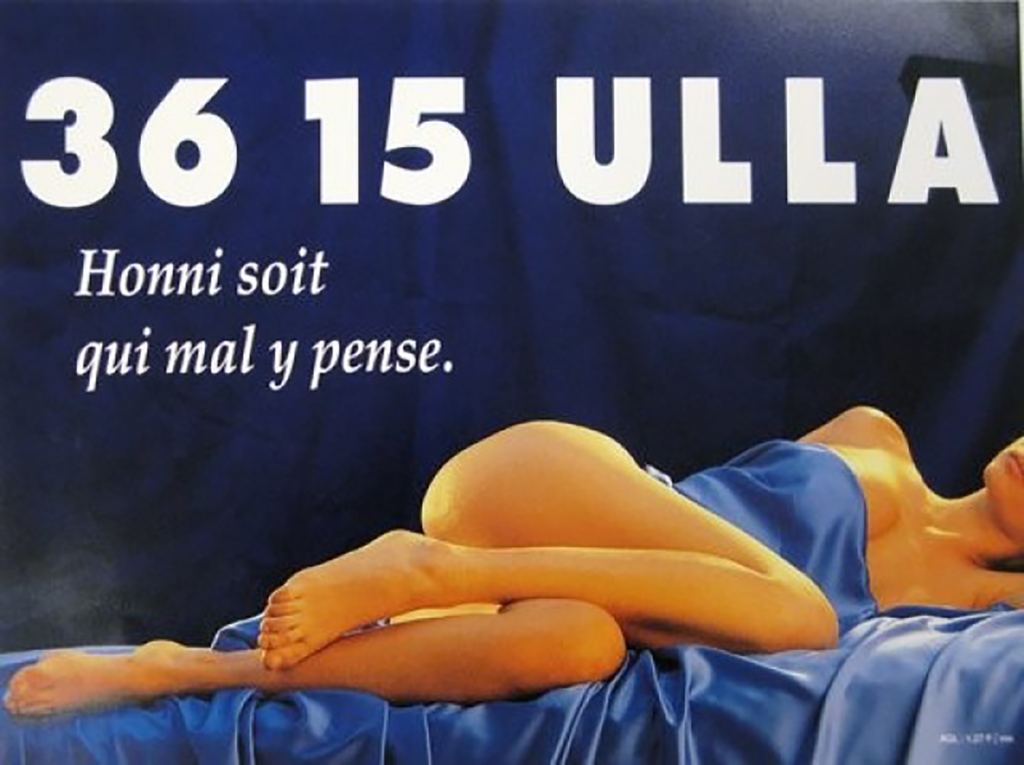

One of the first mass available iterations of the Internet, the minitel, already created deviant spaces for the expansion of the self. Similar teletext systems existed in most western countries, but the minitel was the most popular one. It was a text-to-text platform that proliferated in France as a form of computerized telephone book. But as every invention put into the hands of thousands of people, it was mostly used for an unintended purpose. One of the many different systems to exchange anonymous text-based sexual encounters in real time was the Minitel Rose.

It exploited the anonymity and popularity of the system in France. Both parties engaged into an ‘identity play’, where gender was assumed but never confirmed. As a result, many of the people working for the Minitel Rose were men pretending to be perky sexy women, tricking the user into its own imagination.

“The instrumental computer […] is also a subjective computer that does things to us– to our view of our relationships, to our ways of looking at our minds and ourselves.”§ Turkle, in “Our Split Screens”, unfolds the double game of computers as assistive tools and as transformation outlets. By hacking our biological entity, computers expose the beginning of the metamorphosis of the human into a cybernetic entity, becoming an independently hologrammic human that disembodies itself in asynchronous cyberspaces with different personalities, images, genders or races. Curiously, our active existence in cyberspace is utterly dependent on our existence in reality – it is true that death is less meaningful online than it is offline; if one dies, one’s Facebook and other existing profiles or personae in the web remain a part of the web, but they remain inactive, they are neither upgraded nor maintained, hinting the other users that they are not materially present on the platform anymore. Humans embody information; they process, translate and become readable data to the right choice of sensor, attributes that depend on the materiality of the body, making a ‘complete digital migration’ impossible (for now). Echoing this relation between immaterial and material bodies, McKenzie Wark, in “A Hacker Manifesto”, says that “Information can exist independently of a given material form, but cannot exist without any material form. It is at once material and immaterial.”¶

The Internet, blank stretch of constructed imaginaries, is an impalpable territory where identity multiplication, transformation and/or fragmentation is innate to the medium. Entering the Internet social platforms demands a choice in the person, the animal, the thing we want to be. Integrity is created, propagated, but incredibly enhanced with the appearance of social media. Social media creates a world where all internet-shaped personalities converge in the same platform, confronting their real attributes and their virtual ones. The immediacy and self-framing of these media creates an uncertainty of reality. People are often more inclined to judge someone’s doings by their Facebook’s wall feed rather than by their actual situation in real life. What used to be a key component of the gamer persona (online presence) is now extended to the rest of the world. Indeed, social media renders online presence as important as offline presence in a juggling dynamic between real and virtual, while developing a new architectural form based not on different identities, but on the cult of the self, giving reason to Turkle’s argument on the Internet as a social laboratory: “The Internet has become a significant social laboratory for experimenting with the constructions and reconstructions of self that characterize postmodern life. In its virtual reality, we self-fashion and self-create. What kinds of personae do we make? What relation do these have to what we have traditionally thought of as the ‘whole’ person? Are they experienced as expanded self or separate from the self? Do our real-life selves learn lessons from our virtual personae? Are these virtual personae fragments of a coherent real-life personality? How do they communicate with one another? Why are we doing this? Is this a shallow game, a giant waste of time? Is it an expression of identity crisis of the sort we traditionally associate with adolescence? Or are we watching the slow emergence of a new, more multiple style of thinking about the mind?”#

Web 2.self

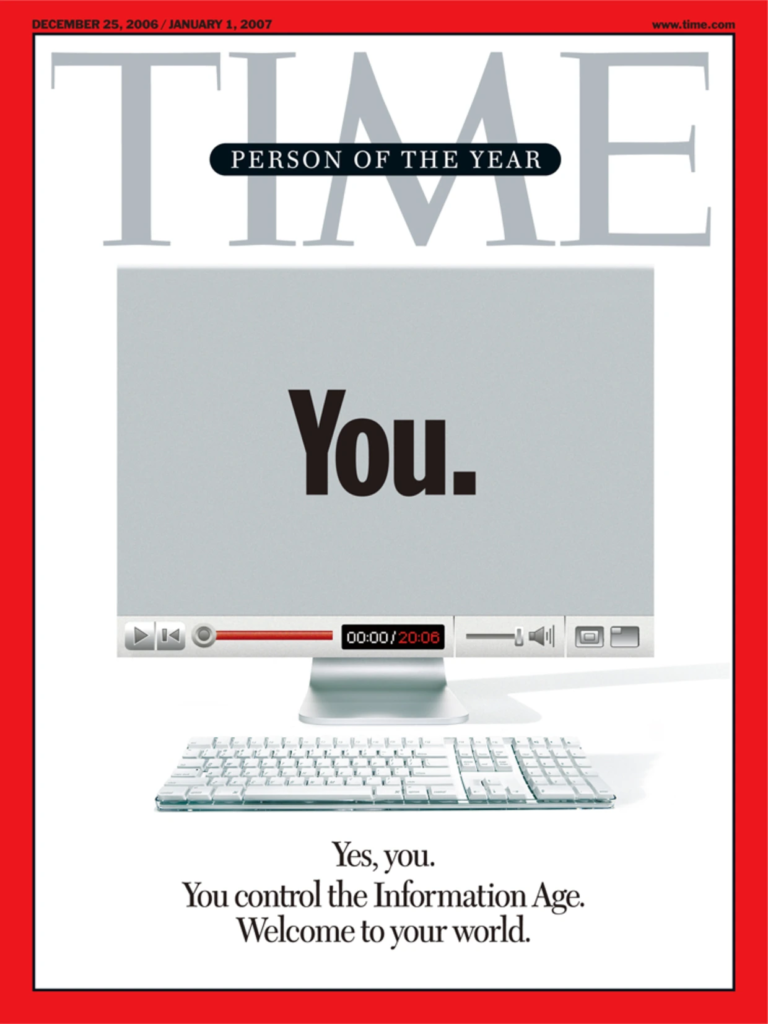

In 2006, Time magazine issued “You.”, a cover that read “Person of the Year – You. Yes, you. You control the Information Age. Welcome to your world.” and acknowledged user generated content in sites like Wikipedia, YouTube, MySpace, or Facebook as a phenomenon that ensured the growing expansion of the Web.

The article, written by Lee Grossman, reads the subtitle: “In 2006, the World Wide Web became a tool for bringing together the small contributions of millions of people and making them matter” pinpointing the spirit of collaboration and community manifested throughout the Web.

This cover was chosen years before, in 1982, the personal computer won the title of ‘Machine of the Year’, replacing what was usually given to a human being. It’s hard to see a coincidence in a choice that illustrates the mutating process between computers and humans! The “You” cover emphasizes the scale, the passion and the narcissism of the human work-force developed by the virtual disembodied structure of the Internet, only a year after the launch of Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, a virtual factory of hidden human labor for computer tasks that computers fail to complete. The MTurk is the one example that shows to what extent the immateriality and invisibility of the Internet transforms social systems and the individual nucleus. The human is reduced to the level of the machine in exchange of a few cents per task. Humans accomplish a series of HITs (Human Intelligence Tasks) that computer algorithms of different sort of firms and corporations fail to achieve accurately –such as recognizing pictures or describing situations, selecting or generating a series of tags, etc– in the environment of a computer interface, without ever interacting with another human and instead diminishing their ambition to ‘becoming a part of an algorithm’. In this case, the individual is not conditioned by the technology in question, but becomes the organic smart-equivalent of an automated computational process. The MTurk is another sort of collaborative system, a darker one, where human labor is unrecognized, hidden in the invisible labyrinth of online virtuality. It is a system that imitates the one that already exists in the real world, taking advantage of the extensive n dimensional spread, of the inconsistencies and discontinuities of cyberspace. Unlike the service generated by the MTurk, the “You” cover refers to the voluntary service of millions of people whose actions and reactions generate a repository of free and open-source content in all domains of expertise and ‘amateurship’. But it does not only refer to a large-scale collaboration. “You” is directed to you, to the individual, the fragmented person, the multi-hologrammic human present in different spaces at the same time, the narcissist. Social media are a widespread phenomenon that form social spheres with different constructs than current non-virtual societies. Instead of representing a group of people (like a country or a culture), these small but numerous spheres represent the entirety of the elements that form an individual, considering multiple identities as a factual constituent of the person. They are social constructs created around the one person, their beliefs, values and philosophy, therefore encouraging a thorough ritual and cult of the self. In “The Interface Effect”, Alexander Galloway refers to the interface as a “trauma – in the psychoanalytic sense – as a necessary cutting that is constitutive of the self.” that engenders a simultaneous “subject-centered induction of world experience – in the phenomenological sense. The interface effect is perched there, on the mediating thresholds of self and world.”**, implying that the web 2.self results from the traumatic experience that bright, titillating interactive surfaces enact on our bodies and minds. The “mediating thresholds of self and world” is particularly suggested by social media personalities, honed and curated to better the image of the self. They reflect the unachieved expectations we put upon ourselves, they represent a mirror that reflects the past as well as the ‘prettier’ version of the self. The insecurities we try to hide with pictures and status updates are often made more obvious because of the ultra-perfectionist curation of information allowed through the ‘self-filter’. For example, what can you think of a girl that only shows pictures of herself at parties and status updates that constantly reinforce how active and healthy her lifestyle is, seemingly sheltered from imperfections and distress? But for this girl and for her circle of cyber-friends, she represents the most perfect image of what she attempts to be. Of course, other types of personality are part of the movement, like people who need constant approval, or others who look for acceptance and validation.

All these types of (im)perfect personalities create the construct of a new social architecture based on the self, on narcissistic belief systems that are in turn part of each individual reality. Called by some a prophet of the technological age, Marshall McLuhan starts his chapter The Gadget Lover of “Understanding Media” with the following explanation of the Narcissus myth: “The youth Narcissus mistook his own reflection in the water for another person. This extension of himself by mirror numbed his perceptions until he became the servomechanism of his own extended or repeated image. The nymph Echo tried to win his love with fragments of his own speech, but in vain. He was numb. He had adapted to his extension of himself and had become a closed system.”†† A study entitled: “The Big Five, self-esteem, and narcissism as predictors of the topics people write about in Facebook status updates” analyzes personality types in relation to Facebook status updates. The study shows how certain types of persons are more keen to share certain types of content. Indeed, low self-esteem users will tend to update more frequently about their romantic life, whereas those considered open individuals will share more intellectual topics‡‡. The machine that feeds the ego, slightly tackled by this study, but more emphasized by another one entitled “Self-Presentation 2.0: Narcissism and Self-Esteem on Facebook” is examined as a way to uncover how the amount of “likes” and comments affect a generation that increasingly believes in narcissism, self-esteem and self-promotion as a means of success in over-competitive environments or lifestyles. The studies show that a considerable amount of young people are driven by their ego when confronted with life-decisions or challenges§§. The Web expands the water pond, the reflective surface that traps Narcissus with his own image, and Sherry Turkle perceives the potential fictional digital worlds can exert on the self through video game culture. In “The Second Self – Computers and the Human Spirit”, she says: “Like Narcissus and his reflection, people who work with computers can easily fall in love with the worlds they have constructed or with their performances in the worlds created for them by other. Involvement with simulated worlds affects relationships with the real one.”¶¶ Sherry’s statement became increasingly true as games started to become more popular and with the appearance of social media platforms. This new social construct shows, externally, an ever-growing collective power although internally hiding a vile mechanism of control unknown to many or as written in the introduction of TechGnosis: “Information Technology tweaks our perceptions, communicates our picture of the world to one another, and constructs remarkable and sometimes insidious forms of control over the cultural stories that shape our sense of the world”##.

Control, in its many forms, is usually and instinctively centralized. Governments for example, even if depending on political systems, are constituted of powers divided among different institutions, they are all connected and respond to each other. From a more detached view, the government and all its separate institutions are one central point of order and control. Even the Internet can be examined as a centralized form of control. The Panopticon is a building designed by philosopher and social theorist Jeremy Bentham in the late 18th century where the inmates could be observed by one single, central person. Foucault describes the Panopticon as “a machine for dissociating the see/being seen dyad: in the peripheral ring one is totally seen, without ever seeing; in the central tower, one sees everything without ever being seen. It is an important mechanism, for it automatizes and disindividualizes power.”*** Even though the metaphor can be contested, for the sake of the argument, the Internet and its growing systems of surveillance and data appropriation seem like a perfect disembodied Panopticon. The peripheral ring is enacted by the everyday user, who is unaware of the surveillance mechanisms fed by each of its actions, while the central tower illustrates governments, intelligence agencies, corporations or hackers that ‘see everything’ and every action. Social media, on the one hand, keeps the structure of a central headquarters. Developers and owners of the company are in control of its evolution, of the layout, of the permissions and freedom tolerated. Nevertheless, on the other hand, it breaks the notion of centralized control through its multi-individualistic structure of self-driven profiles. Our ‘likes’, ‘loves’, ‘laughs’, ‘angries’ or ‘cries’ and our choice of clicked feed generate information that can be easily used by deep-learning algorithms to sort the data to the preferences it considers ideal to our profiles. This data goes back to the central tower of control. But what really controls the whole system, is our interaction with the buttons, articles, and the whole platform in general. Without its user, the company dies, and this interaction is purely driven by our egos. The only reason to go on Facebook or Instagram is either to like someone’s picture or status, boosting their ego, or to promote our own augmented identity, feeding our own ego. Even if the intention is purely intellectual or aimed towards awareness, the system of “likes” seems to drag us into a narcissistic loop that keeps the engagement with the platform continuously active, finding ourselves trapped in the most embarrassing situations of self-validation: compulsively checking our likes or scrolling through “pictures of myself”. These actions are ambushed in a feedback loop where the system keeps generating more content to interact with. Through this structure, users are cellularized in fragmented spaces and individual times, promoting a sort of ‘my reality is not yours’. The cellularization of social interactions is an effective way to avoid forms of spontaneous and rebellious self-organizations like the first unions, for example. But even more is the control each individual grants the system because of their own ego. To fight the current online, virtual corporative system that englobes in its strategy trends, behaviors, and comfort, there must be, first of all, a massive individual reflection on the role of the narcissistic power we voluntarily bestow on the system, which seems like a rather ambitious deed. How do you fight your own self, your pride and your ego when you don’t even realize these are the feelings that drive your ambition? How do you convince millions of individual spheres to stop liking pictures and crash social media when most people don’t even think fighting for privacy rights is worth the effort?

New Mega-Structure: Chaos, Hope and Mysticism

“Twitch Plays Pokémon” (TPP) is a very peculiar channel that was issued in 2014 on the website Twitch, a video, broadcast and chat platform for gamers. TPP was not only a broadcasted video, it was also an interactive stream where all Twitch users could perform synchronously to alter the development of the story in real-time, that led to the becoming of a social experiment with unexpected proportions (over 1.16 million participants and 55 million viewers according to Wikipedia). The story in question was an iteration of the 1996 Nintendo Game Boy software “Pokémon Red”, with a script that converted specific messages in the chat room into directional or selective inputs in the streamed game. As a result, the entire chat room was able to control in real-time and at the same time the player of the game which translated in an erratic series of difficulties, bugs and challenges expressed by Andrew Cunningham in an article entitled “The Bizarre Mind Numbing Mesmerizing Beauty of Twitch Plays Pokemon”: “Red gets stuck in corners. He walks in circles, compulsively checking his Pokédex and saving over and over again. Commands stream in from the chat channel faster than the game can possibly process them, making progress difficult-to-impossible even without the lag factor or the ‘help’ of gleeful trolls.”††† Eventually, it led to big scale coordination accidents like the one known as the ‘Bloody Sunday’ where twelve pokémons were accidentally released. The importance of this experiment, besides the playfulness, difficulty (attribute always in the look-out for gamers) and unexpectedness it provided is the resultant (instinctive) organization and collective synchronization that the massive scale of users had to enact to be able to finish the game, ordeal that took 16 continuous days of gameplay. Overcoming the unpredictable expansion and chaotic interaction of the stream, 1.16 million participants reached a common shared goal that could only be achieved through persistence and severe organizational skills. Moreover, the anonymity of the creator is incredibly relevant to the experiment, highlighting the internet-enhanced duality of belonging to a decentralized movement of masses while finding individual expression. Indeed, if the programmer was to disclose their identity, the collective purpose of the game would fall apart, as it would fulfill the satisfaction and desire of one individual. The mystical characteristic of the developer gives the idea – and hope to some – of a higher purpose, almost as if the web itself simulated its ambition, dawning in chaos but developing into the possibility of a future collective hive-mind. TPP (and by extension the Internet) can be considered an unexpected example of french sociologist Emile Durkheim’s take on holistic groupings. In his 1912 book “The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life”, he precisely mentions how collective social experiences are channeled through religion and rituals, blending in moments that solidify the community. In an attempt to update Durkheim’s theories to a 21st century context, TPP and moreover, the Internet experience can be interpreted as a substitute for religious congregations: a community experience residing in mutual mysticism, a shared trance where we are one. Furthermore, though diametrically opposed, Max Weber’s views on society might help illuminate the Internet mysticism phenomenon even more. The Internet is a place that invites paradoxes and oxymorons to co-exist and by doing so Weber’s take also illustrates the mystical Internet experience. Indeed, Weber talks about the disenchantment and demystification of a world driven by science and proof as a world that lacks (yet needs) magic and mythology, therefore highlighting the need for a shared, communal experience that might give to the individual the enchantment it craves‡‡‡. 86 years later, the mythical remains an essential idea to the understanding of human-created systems, leading Erik Davis to write “TechGnosis: Myth, Magic and Mysticism in the Age of Information”. The Internet, a place where we can be simultaneously in touch with millions of people, reflects a lot of Weber’s and Durkheim’s ideas, making it a quasi-religious experience.

Besides its similarities with belief systems, the Internet is a place that develops its own wilderness. George Dyson compares the evolution of DNA to the evolution of computer programming§§§. He defends that it is all about setting a language, an alphabet and letting it surpass challenges: indeed, jumping from a bacteria to a lizard demanded some intense modifications of the original code. In the same way, computers learn from us without us being aware of how much they understand, and it is exactly when the machine does things that we do not fully understand that intelligence can emerge. Machine learning can be interpreted as an iteration of the wild web, the natural, interesting, unpredictable space that rises from the evolution of the binary digital alphabet. In a way, the wilderness of the Internet are all the unexplored sub-layers of possibilities, the hidden chunks of information that are yet to be decoded, or the inaccessible to the human brain. If conscious machines were to appear, it is possible that they would start to emerge from. Machine learning can be seen as a technical ramification of ‘deep’ systems used for machine learning research, like deep belief networks (a probabilistic generative model), deep Boltzmann machines (an undirected probabilistic graphical model), etc. where “deep” can be interpreted as the depth of calculations necessary to create said systems. Even if humans understand well enough the concept of the algorithmic challenge to create a program that can run them, these extent calculations are only truly comprehensible to the machine that besides computing also learns and enhances its results with incoming data. To what point can it learn and enhance its efficiency? Maybe to consciousness, unless it only remains a machine. In that sense, machine learning effectively expands into wilderness, an attribute that, as Dyson argues, renders the virtual universe even more interesting.

The wild web gives rise to mega-structures based on collective actions and generated content. On that train of thought, I would like to propose the following (small) manifesto for the meta-conscious being:

~: elements of transformation

~: a continuous evolution

~: wilderness and

~: adaptation

~: _the human, an endless experiment of an outer space species

_the meta-conscious being

_consciousness is but a mere glimpse of a higher system of awareness

1_the meta-conscious ‘human’ is not a center, but an element, part of a mega-structure

2_the individual has been abolished

3_one does not think for oneself anymore, one thinks for the structure

4_the structure is similar to a mega-brain composed of billions of ‘brains’

5_based on the model of the octopus and its alien DNA, each part of the mega-brain acts as a brain itself

6_the supremacy of Intelligence is reached through the neural system used at its full potential for each individual component of the Mesh

5_earth is not our habitat, we inhabit the entire galaxy

6_our physical form has been abolished

7_when belonging to the Mesh, physicality is an absurd concept

8_our materiality has been reduced to the bare minimums of survival of a species, for the only purpose of nurturing the Mesh

9_we are super adaptive organic blobs

10_we can now live in space, in gaz, in extreme heat, in extreme cold, underwater, in toxic environments

11_we do not care, because we are not one, but a whole

Conclusion

“space,

time,

dimension,

becoming,

future,

destiny,

being,

non-being,

self,

non-self,

are nothing to me;

but there is a thing

which is something,

only one thing

which is something,

and which I feel

because it wants

TO GET OUT:

the presence

of my bodily

suffering,

the menacing,

never tiring

presence

of my

body”

(Artaud, 1947).

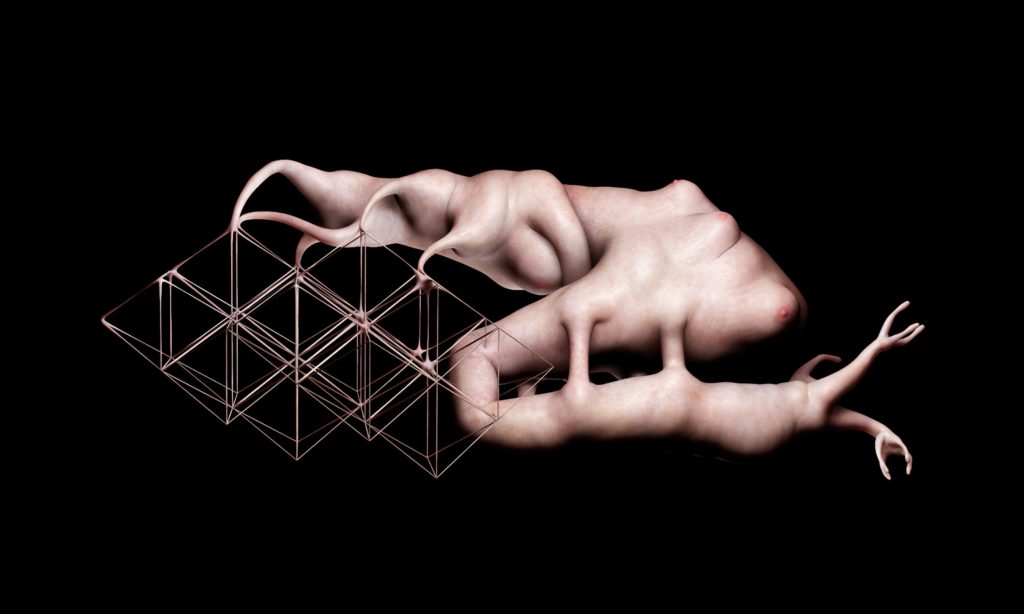

This passage from Artaud’s “To Have Done With the Judgment of God”, refers to the existential interdependent pain of being confined to the flesh vessel that is the body. Ashamed of his materiality, he reduces it to the expression of a smelly fart therefore diminishing the bodily existence to an ephemeral and proliferating –disgusting– form. The body, if not annihilated, must be distorted. Right before, he talks about “dilating the body from my internal night, from the internal void, from myself” as an explosive necessity. He tries to understand the duality between body and soul and achieve its final form: a body and a soul instead of a body with a soul. I wonder what he would have said of the Internet, of the disembodied virtual self, of the multiple I, of the compulsion with the self. The inter-, the between, the reciprocal is but a screen that transforms and distorts the continuity of the organic into the discontinuity of the digital. Each screen encountered in the world of the digital is a layer of distortion that traps the image into an infinite fragmentation of its essence: a fractalization. It is the photo of a photo of a photo seen through a screen through another screen through yet another screen. From the “real” side of the screen, the reality of the human is sensorially doubted, yet somehow certified as true. When the distortion affects reality, it is not a fragmentation that is perceived, it is a continuous deforming process, a “smudge tool” of sorts. When the skin blends with technology or when technology acts as a second skin, the distortive process amalgamates elements from both worlds into a reconstructed oneness. This dilating skin that acts as the symbiosis of two different dimensions introduces a new language between both worlds. How does the symbiosis interact with the purely organic, with the purely mechanic, or with the purely virtual? The future, maybe fictional mutation endured by humankind through technological advancement has a new expression, one that defines the new hybrid, one that abandons the human and the machine for other becoming, for new constructions, for inconceivable futures. Machines are left as the hollow, perhaps (in)active remains of human dreams and expectations, the “sacred” remembrance of the organic human… relics of our humanness.

Bibliography

Berardi, F. B. (2009). Precarious rhapsody: Semiocapitalism and the pathologies of the post alpha generation. London, UK: Minor Compositions.

Bolter, D. J. & Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation: Understanding mew media. Massachusetts, MA: MIT Press.

Bostrom, N. (2008) Letter from utopia. Studies in Ethics, Law, and Technology, Vol. 2 (1), p. 1-7.

Chromapark, E.V. (1995). Localizer 1.0, The Techno House Book. Berlin, DE: Gestalten.

Cunnigham, A. (2014, February 18). The bizarre mind numbing mesmerizing beauty of twitch plays pokemon. Ars Technica. Retrieved from: https://arstechnica.com/gaming/2014/02/ the-bizarre-mind-numbing-mesmerizing-beauty-of-twitch-plays-pokemon/

Durkheim, E. (1995). The elementary forms of religious life. (Fields, K. E. Trans.). New York: The Free Press. (Original work published 1912).

Grossman, L. (2006, December 25). You – Yes, You – Are TIMES person of the year. TIME. Retrieved from: http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1570810,00.html

Hayles, K. (1999). How we became posthuman: Virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ipeirotis, P. G. (2010). Demographics of mechanical turk. CeDER Working Papers. Retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/2451/29585

McLeod, K. (2003). Space oddities: aliens, futurism and meaning in popular music. Popular Music, 22(3), 337–355. Retrieved from JSTOR.

McLuhan, M. (1994 [1964]). Understanding media: The extensions of man. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Mehdizadeh, S. (2010, August) Self-Presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 357-364. http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1089/cyber.2009.0257.

Musser, G. (2016, February 25). Consciousness Creep. Aeon. https://aeon.co/essays/could machines-have-become-self-aware-without-our-knowing-it

Saville Productions (Producer), & Herzog, W. (Director). (2016). Lo and behold: Reveries of the connected world [Documentary]. United States: Magnolia Pictures.

Searles, R. (2016, December 21). Virtual reality can leave you with an existential hangover. The Atlantic. Retrieved from: https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2016/12/post-vr-sadness/511232/

Steyerl, H. (2012). The wretched of the screen. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

Stroll, A. & Martinich, A. P. (2017). Epistemology. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved from: https://www.britannica.com/topic/epistemology/The-history-of-epistemology

- *~Aardema, F., Cote, S., O’ Conor, K. (2006). Effects of virtual reality on presence and dissociative experience. *CyberPsychology & Behavior*, 9(6), 653s.

- †~Bridle, J. (2012, October 16). Living inside the machine. \[Blog post\]. Retrieved from: [http://booktwo.org/notebook/living-inside-the-machine/](http://booktwo.org/notebook/living-inside-the-machine/)

- ‡~Davis, E. (1999). *TechGnosis: Myth, magic and mysticism in the age of information*. London, UK: Serpent’s Tail., 247

- §~Turkle, S. (2002). Our split screens. *Etnofoor, XV (1/2)*, 5-19. Retrieved from JSTOR., 106-107

- ¶~Wark, MK. (2004). *A hacker manifesto*. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- #~Turkle, S. (1995). *Life on screen: Identity in the age of the Internet*. New York: Simon & Schuster Trade., 180

- **~Galloway, A. R.. (2012). *The interface effect*. Cambridge: Polity Press., viii

- ††~McLuhan, M. (1994 \[1964\]). *Understanding media: The extensions of man*. Massachusetts: MIT Press., 41

- ‡‡~Marshall, T. C., Lefringhausen, K., Ferenczi N. (2015). The Big Five, self-esteem, and narcissism as predictors of the topics people write about in Facebook status updates. *Personality and Individual Differences, 85*, 35-40. [http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid](http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.paid). 2015.04.039

- §§~Mehdizadeh, S. (2010). Self-presentation 2.0: Narcissism and self-esteem on Facebook. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 357–364. [https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0257](https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0257)

- ¶¶~Turkle, S. (2005). *The second self: Computers and the human spirit*. Cambridge: MIT Press. (Original work published in 1984)., 81

- ##~Davis, E. (1999). *TechGnosis: Myth, magic and mysticism in the age of information*. London, UK: Serpent’s Tail., 4

- ***~Foucault, M. (1995). *Discipline & Punish: The birth of the prison*. (Sheridan, A. Trans.). New York: Vintage Books. (Original work published 1975)., 212

- †††~Valentine, J. (2014, February 25). Bloody sunday in Kanto – This week in twitch plays pokemon. *GameZone*. Retrieved from: [http://www.gamezone.com/originals/bloody-sunday-in-kanto-this-weekend-in-twitch-plays-pokemon](http://www.gamezone.com/originals/bloody-sunday-in-kanto-this-weekend-in-twitch-plays-pokemon)

- ‡‡‡~Weber, M. (1992). *The protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism*. (Allen and Unwin, Trans.). New York: Routledge. (Original work published in 1930).

- §§§~Viviani, A. (2016, August 26). La technologie possède les qualités que nous cherchons dans la religion. *L’OBS Rue 89*. Retrieved from: [http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/rue89/rue89-le-grand-entretien/20160826.RUE7942/la-technologie-possede-les-qualites-que-nous-cherchons-dans-la-religion.html](http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/rue89/rue89-le grand-entretien/20160826.RUE7942/la-technologie-possede-les-qualites-que-nous cherchons-dans-la-religion.html)