Something we share as professors of performance studies and history is a commitment to embodiment in pedagogy. Historian Peter Sebastian Chesney was inspired by artist Jeremy Hahn to craft a UCLA writing seminar called “Sensory History: Touch.” Over the months, Hahn and Chesney kept discussing this method as they learned through experience and visited one another’s classes. Now they have written a dyadic essay detailing remote pedagogical strategies and reflections while teaching on zoom. Each of these two educators shares ideas about how to help students stay with their senses and bring their bodies along even in the context of the digital classroom. First, they enacted demonstrations of touch in the digital age by mindfully using the fingers (Chesney taught with his smartphone in hand during historical walking tours), by keeping on the feet (Hahn danced in a constructed at-home dance studio), and facilitating talk about internal feelings of sensitivity to their course content. To those who worry a lack of face-to-face education during the recent lockdown led to a sense of disconnection for all students and all faculty, Hahn and Chesney created practices fostering embodiment in zoom teaching. What we present is a point against arguments for delaying any future lockdowns for the sake of maintaining the highest quality of college-or-university-level coursework. In the middle of this crisis, we embraced embodied pedagogies, which led to innovations in how we teach.

***

JH (t | he | y) – Introduction

The delicate feel of touch. Fingertips against the smooth surface of the keys typing these words. My body’s weight touching the seat beneath me, and the heat of the surrounding early summer air amplified by the enclosure of my live/work artist’s studio. As I sit; this body remembers the forest and the rhythms of the land. The meditative memory of trees, water, and sky where I was for a week residing in the embrace of the earth for the first time after over a year of quarantine, stay-at-home, and social distancing orders. Inhaling now; I breathe the stale air of trains passing the depot across the street, the exhaust from three adjacent freeways, and all the noise of contemporary commerce. I imbibe the freshness of pines and the clean air in my mind’s eye. All the complex systems housed by the boundaries of my flesh are of the earth and space. Yet, when willingly placed back in my fabricated container of the human-made world, the remembrance of the earth can slip. The night sky ablaze not with stars in the city of angels, but of neon lights masking the cosmos from view. An ever-present sonic pulse rings constantly in my ears. I feel languid as my face glows, receiving the light of this screen. This two-dimensional portal opens a window to the world, and becomes the object that links me to others. I close my eyes, breathe, and imagine the past year as an artist and an educator during the pandemic and how it’s shifted the boundaries of how connections can be made – sensing touch, though not quite touching.

PSC (he / him / his) – Introduction

This is a dyadic essay pairing poetic observations with didactic analysis. From what follows, you will see how we taught in the pandemic year of 2020 what we are calling a pedagogy of embodiment. What we have proven is that zoom is no excuse for disembodiment and detachment. In fact, we invented new ways to bring the body online and to come back to our senses, remotely. Face-to-face instruction is lovely, but it is also a luxury. The next time our campuses need to consider a lockdown, worries about whether professors can provide quality college or university education are no longer a valid excuse for delay.

I have been a student of Jeremy’s, and his collaborator. We first met at a now-demolished viaduct leading to the concrete floor of the L.A. River. Jeremy and SkyE created a participatory dance experience down there. As the years passed, I kept going to see what more they had to offer: classes at Camera Obscura Art Lab and an experience under the Colorado Street Bridge created with his partner. For that latter event, I composed a land dedication and read it as our group began a site-specific dance and song performance or “offering” in the Arroyo Seco.

This context is essential to understanding how our collaborations would eventually shape the remote history seminar I developed for COVID times at UCLA. I gave the course the title “Sensory History: Touch” only in part because I consider myself a sensory historian who has written a sensory historical dissertation. Another significant reason is that I was inspired by the teachings I learned from Jeremy about embodiment, which had helped me come back to my senses after a long immersion in reading theory as a graduate student in the social sciences. Before the pandemic, my practice as a professor had always been to assign students hundreds of pages of dense reading and to take seminar as the time for us all to come together and to unpack it.

Now that we were not going to be meeting in person, I endeavored to switch gears for this new course called “Touch” where we were to make our fingers, our feet, and the internal feelings of our bodies into the primary sites of historical investigation and meaning making. This pedagogy amounted to an answer to the great technologist – and technophile – Howard Rheingold, who once claimed, “people in virtual communities do just about everything people do in real life, but we leave our bodies behind.”* Through dialogue with this dance professor, I was also able to teach a history with my body, written on my skin, in my footprints, and in the signals fired between my brain and other internal parts of my body.

Fingers: how did you use your hands when you taught remotely?

JH – Fingers

“All that you touch you change / all that you change, changes you.”†

Octavia E. Butler

Our fingers are one of many bridges connecting our bodies to the outside world. We reach for nourishment, caress a cheek, and grip handles, opening doors to newness. When we desire something, we extend our arms and unfurl our fingers. Like antennae, we can sense the world with our fingertips, experiencing wisdom along the way. With our uniquely miraculous hands, we can choose to embrace a process of learning. One could pick up a book, type a question into a search engine, send in an application to a school, or physically open the door to a classroom. When we choose to open the door, we pass through a threshold into a new performative life role. The role of a student or teacher. This opening and entrance is a conscious act of participation in the pursuit of knowledge. When we step into a class, we open into a space designed for learning, collaboration, discussion, and inquiry. With unique and refracted motivation, we arrive in the room. This motivation is the reach, an opening of the hands, and a gathering of materials and self. With active engagement, this becomes a practice of embodiment. The context for learning shifted predominantly online during quarantine, dissolving some of the traditional histories of embodiment students developed during their many years of physically attending school. This drastic transition created new digital thresholds to pass through: asking students and teachers to embrace adaptation, feel out this new terrain, evoke lineage, and collectively make new innovations along the process of learning.

As an educator of dance at Cal Poly Pomona the move to remote learning became an opportunity to redefine the classroom while continuing to inspire connection digitally so we could dance apart, yet together. Students no longer transported themselves to campus but instead typed in zoom IDs and entered into new creative and academic digital landscapes. Picking up and positioning digital devices became the threshold for the students to pass through. The “contact zone”‡ of the zoom space became the bridge linking our living spaces and converging our realities in pixels. The narratives of our lived spaces were being rewritten by our dancing. Any space in a home could become a dance studio and inspire unique and creative movement. We began to see each other in new ways, dancing in various rooms, surrounded by our personal or familial décor and animal companions. The liminality of the dance studio became a memory, and we were now required to navigate space in new ways. The dance studio was a shared experience where we could move freely unencumbered by obstacles. We would feel the energy of bodies moving nearby and experience the group pulse within the empty room. The studio was a place of potential. The loss of this open empty space left us contained in our rooms and yet we began to understand this forced us to try new things and be creative. In the initial months of lockdown, we felt a myriad of uncertainties, and we contributed our experiences through the offerings of movement, voice, and typed reflections in the chat box. As scholar and activist bell hooks states in her text Teaching to Transgress, “One is inspired to persevere in the presence of others.”§ We showed up for one another and our presence became this affirmation to continue on and cultivate embodiment as a community in a two-dimensional classroom. Although we were flat on screens, the dancing helped bring us into a state of wholeness, movement, and adaptation to change.

To assist with this process, as an instructor, I held the intangible container for each class creating an inclusive digital space to cultivate learning and the development of deeper movement awareness. Dance classes prioritized the digital touch of community connection and the remembrance of our interconnectedness. We were in an unknown period hearing disinformation about the ending of a pandemic that continued to rage. Counteracting this looming fear that threatened to freeze our bodies we chose to dance. Our bodies reached and stretched. We extended our energy, improvised, moved with one another, choreographed in intimate groups, and navigated within small spaces. These activities were performed with the intention of building, and maintaining, a temporal ensemble community, which is an important aspect of my pedagogy. Dance is individually personal and simultaneously communal. While dancing digitally, we could no longer feel the collective heat, the moments of brief contact with other bodies, and the feeling of air rushing past an ensemble. These sensations all had to be imagined. When accessed, the somatic memory of dancing with others still reverberates in our bones. We recalled this memory while moving through the dance of embracing the unknown present.

We were in a new moment of dance education. I was moved by the numerous resources provided by dance educators via online media and evoked the presence of our own unique ancestors within our movement vocabulary during class. We flipped upside down, reached directly in space, passed energy to each other, and carved the edges of our kinesphere with our fingertips while surrendering into gravity. With the assistance of the internet, we also had the opportunity to view historical and contemporary modern dance choreographies while many institutions opened their doors to footage, classes, and realized pieces of art not usually available to the public. In particular, two works from choreographers Trisha Brown and Merce Cunningham resurfaced with newly added tutorial instruction by their company members. In particular, Brown’s Roof Piece (1971) was originally performed by her ensemble who stood atop buildings which spanned many blocks in New York City passing movement to one another like playing a game of telephone. During the pandemic, this piece now known as Room/Roof Piece (2020), was shifted by the company. They connected via zoom now divided not by the New York skyline but instead by countless miles of rivers, oceans, and terrain. Although the piece never contained physical touch during its original iteration, there is still a sense of touch felt by the company members as they embody the improvisational “semaphore”¶ movements in a shared vernacular. The company encouraged people to create their own versions of Room/Roof Piece and we did our own rendition as a class. We were touched by witnessing the transmission of movement and participating in the revision of this piece of dance history, reinventing how we dance with one another. Connection could still be maintained through the sonic fibers of the internet mingling with the neural network of our fleshy systems. Our dancing was a process of inscribing new narratives into our somatic and collective memory. As I write these words and reflect back on that time, I realized there is nothing tangible from my experience I can hold in my hands. Just a dancing temporality of shifting sands.

PSC – Fingers

Sensory studies of touch typically begin with the hands. For instance, consider the book series with the title “Hands That Built America.”# The dexterity and sensitivity of hands, at least the ones with a near-normative human range of motion and feeling, make them into amazing tools. Histories of touch thus start with the material culture of objects designed for human hands to pick up, to hold, to swing, to caress, and to throw. We learn about artisans skilled in crafts involving tools and also about proletarians habituated to repetitive motions. We appreciate artists with a mastery for brush strokes or musicians with a talent for picking cords. We cringe at the thought of a soldier’s finger pulling the trigger or captives with chains on their wrists. We read from scholars who thumbed through files of primary documents before selecting the most useful ones for a new study. We turn through the pages of the books they spent years outlining on yellow notepads or typing on typewriters. And during the lockdown, we relied on these capabilities more than ever, especially as educators. Fingers clicked mouses and fingertips tapped touch screens more times per day than previously at any time in the years before the pandemic. These motions were like a worldwide vibration that sustained our teaching for the next twelve months. Indeed, we became utterly habituated to the touch of machinery like laptops and handheld devices.

We also lost touch with many surfaces. Some of us went longer without putting our hands on a car’s steering wheel and driving than ever before in our adult lives. Many forgot what it felt like to shake a stranger’s hand and do not plan to resume this ritual. This sudden, shocking retreat from certain touches was what inspired me to write a curriculum about sensory history. I taught the first iteration of “Touch” in the spring of 2020, the earliest quarter at UCLA without any person-to-person instruction. My students read about such touchy topics as khipus, the Inka tradition of recording and communicating information by encoding it into knots on strings. They also learned that the author, anthropologist Gary Urton, has a cognitive condition that rendered him unable as a Cub Scout to master knots.** Only after decades as an expert on pre-conquest knots did this man realize his motor impairment might be relevant to his long-standing focus on Inka knot makers and his groundbreaking efforts at interpreting their secret codes. His forgotten disability endowed him with a hidden ability, a super power, to notice the tremendous skill in a person of the distant past who was capable of keeping a census or an account of taxes, trade, and inventory by swiftly tying and untying knots by the thousands. With a more embodied pedagogy, he might have come to recognize this about himself earlier in his career. It is terrible to think that touch-aware and sensory-stimulating teaching has been mostly restricted to early education in the years after educators Friedrich Froebel and John Dewey popularized the practice in German and United States preschools at the turn of the Twentieth Century. Play, outdoor education, and the uses of the hands for learning have never quite advanced into secondary- and tertiary-level social sciences curricula.††

One of the foundations of touch history is self-examination or auto-ethnography, upon which I built a method for remote learning. On zoom, which I had downloaded as an app onto my smartphone, I became the model for students when I went into the world and filmed my hands handling all sorts of old things. These included the smooth river rocks on the walls of an 1897 house that writer Charles Fletcher Lummis built for himself in a historic neighborhood of Northeast Los Angeles. I stressed how this White man, a Harvard dropout sick with tuberculosis who walked across the country as a publicity stunt, had touched every rock I touched. In the barest sense, I was revisiting and re-enacting his labor. Slowing down to contemplate the cool hard granite, I came to know and then to describe the energy that went into this effort. I spoke of the number of hands that have held and made all the other stuff in our lives: not only buildings and infrastructure but also the smaller things like prepared foods and electronic devices. Sensory history is thus an essential part of social history, a literature about materiality, everyday life, and the social relations so often hidden from consumers within the things they buy. At the Lummis House, sensory history pried open a door into cultural politics too. As I circled the building, I came to one unusual stone. The largest on the wall, it had a pronounced divot, for it was a Native acorn grinding rock. I told the students Lummis had found it on a hike in the Tujunga Canyon, many miles away in Tataviam country, and brought it home to build into his wall. What if I touched this object, I asked. Would I be echoing settler colonialism when I too touched what Lummis took with his hands, I wondered. This launched the students into a debate about the ethics of stolen Native artifacts. Several of them called for the rock to be returned and repatriated to Tataviam people. To achieve this outcome, I noted, someone would have to touch that rock. They would have to break it out of the wall of this old house. They might even damage the rock beyond the point of repair. Who had the right to do this touchy work of returning a stolen object? Would they have to be from the area’s Native communities? What expectations would they have about being paid to do this work or being trained to do it well? And what about the ethics of having to get permission to do so from the conquerors still in power at Los Angeles City Hall?

It was at this point that I revealed how I came to be in this place. I had no permission. I’d jumped a locked gate. I was trespassing. At that point I shared the course’s critical intervention: during the pandemic, we had to give up a number of our rights, which I was willing to do for the sake of altruism, but I wanted a few new concessions. I was going to constrain my mobility, to cover my face, to stop meeting new people, and to lose my face-to-face social networks. But I was not going to respect fences and locks the way I had in the past. What is called the right to roam in the United Kingdom came to me, and I roamed. If you cannot reach out and touch someone’s hand, then reach out to touch a piece of history, I advised the students. Their first assignment was to hand write letters and to post them to my P.O. box. With time, I grew bolder in this experiment. For a later fieldwork trip, I brought a bag of tools to the Hollywood Walk of Fame. At the star of former President Ronald Reagan; I showed the students the contents of a knapsack: duct tape, a ripe banana, a hammer, and a can of red spray paint. Which should I use to mark Reagan’s legacy, I asked. One student nominated the paint and asked me to put an HIV/AIDS remembrance ribbon on the monument. I had just mentioned how many had died in the great 1980s epidemic, one which all the people saying COVID-19 was unprecedented seemed to ignore. The students saw Reagan for what he had (not) done; they proposed the next step; I made their mark.

Feet: how did you teach by getting on your feet, if you were able, and moving?

JH – Feet

“I have arrived. I am home.”‡‡ These are affirmations spoken by the Zen Master, Thich Nhat Hanh. He offers these simple mantras for practitioners to use during a meditation walk. With each breath and each step one may repeat the mantra. These words and our footfalls return us to the present and remind us that we make impacts on the earth with each step. With concentration, we return to ourselves again and again.

This practice of remembering our wholeness and connection to the earth was greatly challenged during the course of the pandemic. During the initial safer-at-home order our pathways shifted and time in the natural world decreased. Many were not navigating the boundaries outside their homes, but walking paths only indoors. Our feet, used to shoes, may have felt released from their tight confinements, dressing from the waist up became a widespread practice. Stress gripped our bodies and kept us from wholeness. Participating in a dance class is a full-bodied experience. Though we might have to be creative with our device’s location, we did our best to let our entire moving bodies be visible all the way down to our elusive feet. Our feet are our foundation, rooting us to the earth and connecting us to the possibilities of dynamic moving pathways. Teaching digitally during the pandemic, my feet said ‘yes’ to the creative challenge.

The body is sensitive to space, movement, and expression. During this transition to our new makeshift home dance studios, we had to remain adaptive and open to support our bodies. This began with mind, body, and heart connectivity. Class opened with breath and feeling our connection to the earth and space. We felt our feet on the floor in whatever room we occupied. We noticed the texture of the space and objects within and how our bodies felt in relationship to these surfaces. We settled into the dynamic lifting and yielding of our musculature in this new setting. Expanding beyond our physicality, we closed our eyes and imagined ourselves in a circle with one another. Since we could not feel each other physically, we could feel one another energetically. We moved our imaginative capacities into the psychic field to affirm our connection as a community even though we were separated by great distances. With each breath, we expanded and contracted three dimensionally and found a group pulse. We noticed our weight, distributed through the arches of the feet and engaged the oppositional pull of forces on the vertical and sagittal planes of the body. We started slowly some days with walking and basic locomotor actions linked to breath, or we would jump in and pump the energy, darting through space, touching the edges of our rooms with our limbs, and blowing past the framing of our webcams. Guiding these movement improvisations, I watched students drop into the experience over time. Their embodiment, commitment, and focus deepened. They let go into the physical and creative sensations. Students expressed that while moving, their stress and worry dissolved, and this was their first time feeling deeply meditative while dancing. I was reminded of the words spoken by one of the founding mothers of modern dance, Isadora Duncan, who wrote, “The dancer of the future will be one whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of that soul will have become the movement of the body.”§§ This digital world is perhaps a good representation of Duncan’s future dancer, as remote teaching bridges the distances between us through movement to feel the earth in our bones, the blood beating from our hearts, and connecting to something greater than ourselves. We moved to affirm life. Each day we were all on our feet, shifting weight, creating trace forms, etching new pathways, and redefining space. We had arrived, we were home, and we were dancing.

PSC – Feet

While facilitating my UCLA seminar called “Touch,” I found myself going against the grain of pandemic-era education. By this, I mean that I spent over a year teaching on my feet. If you watch the feet, you find a great divide between teaching before the pandemic and after the pandemic started. Professors, if they were able, previously commuted to campus, walked its paths and halls, and then stood before their students during lectures. When COVID-19 came, they almost universally sat down to teach in their home offices while bent a little forward looking into cameras and speaking into microphones on their desktops and laptops. I want to stress that this massive repositioning of the teaching body was not essentially linked to any inherent crisis in pedagogy. To teach remotely is not linked to a loss of standards or a decline in performance. But many who learned to teach from educators who modeled teaching as something you do while standing in front of their students did seem to lose something when they collectively sat down. Confined to chairs, they stopped engaging as wide a range of their muscles and seemed to lose some of that enthusiastic energy they used to exhibit while on their feet.

When professors taught synchronously, we noticed a similar torpor in the students, who oftentimes reclined in their beds while wearing pajamas or simply kept their cameras turned off. The pace of speech seemed to slow with the passing quarters. Students and professors both grew more depressed, more sensitive to setbacks, and less likely to make spoken contributions to class. Of course, their sadness was also a reflection of the many tragedies in the world. Thousands were in the streets demonstrating against police violence. Millions were dying of the virus. Tens of millions lost their jobs. Students and professors were stuck in their homes trying to learn and to teach. Some had to remain muted because of the noise level in the rooms, which they had no choice but to share with others. Others had to censor what they said because they were within earshot of family or friends who might take offense to what was said in discussion. A solution to these problems, I found, was to teach and to learn outside the home.

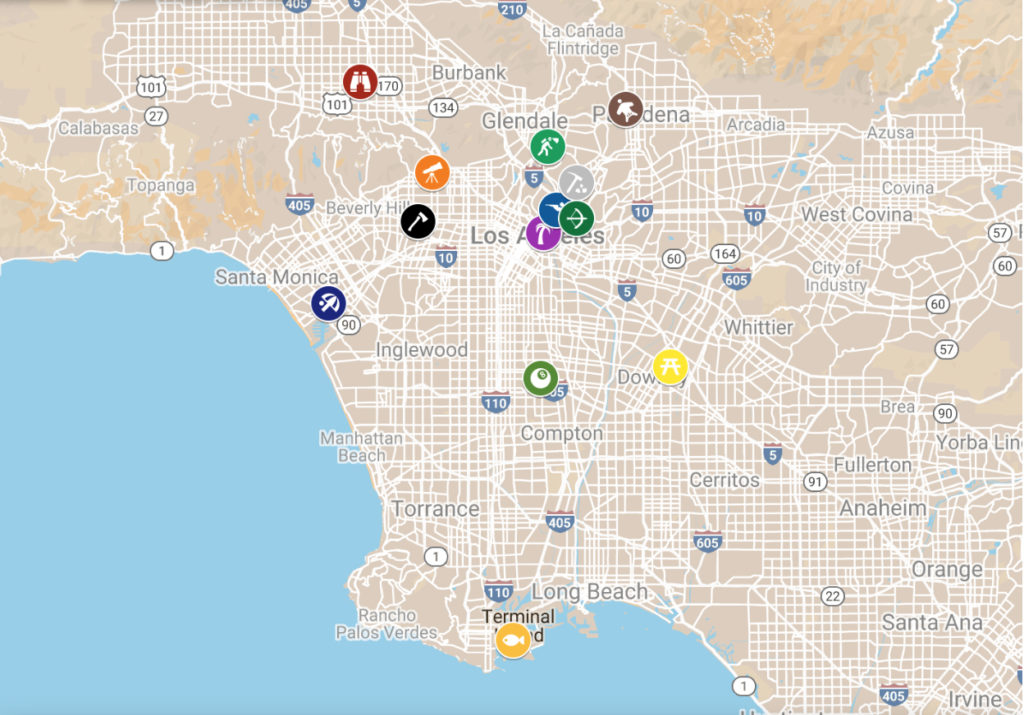

The moment the City of Los Angeles instituted a safer-at-home order, I began to feel terribly confined. Walking, bicycling, bus riding, driving, and exploring have been essential parts of my life in the city where I am from and which I chose as the subject of my history Ph.D. A curiosity about retaining these habits led me to read the city’s order carefully and to notice a list of “essential workers” with special permission to journey out of their homes to do their jobs. College and university educators were on the list. The city excused us to leave and to go where we needed to go to record our courses. Of course, my employers had told us teaching assistants to conduct our classes not on campus but rather at home on zoom. When I realized zoom was available for download on the app store, I did just that and began planning my escape from private at-home confinement back into the public sphere. “Touch” encompassed smartphone walking tours of Los Angeles during which I gave lectures, facilitated discussion, and enacted fieldwork. The students stayed indoors, as ordered by the city and various other local governments, but through my smartphone’s camera and microphone, they saw and heard what was happening outside in Southern California. Vicariously, with the use of my feet and my phone, they overstepped the boundaries enclosing them from city life and saw what quarantine was like in Los Angeles.

Californian’s response to the pandemic was libertarian. More authoritarian societies around the world had much stricter lockdowns than we had in the U.S. In the People’s Republic of China, no one left their homes to work as a professor, let alone as a bank teller or a fast food worker or a cannabis dispensary retailer. Only the most essential workers left home for the sake of policing the streets against wanderers like myself or to deliver food for free to the whole population. My walking tours showed students that in Los Angeles, some places had emptied while others were still bustling. The freeways were clear of commuters, but the Hollywood Boulevard strip had a surprising number of international tourists strolling, gatherings of men listening to music, and housing insecure people begging. With my smartphone, I was able to show the students how two federal prisons in Los Angeles, the Metropolitan Detention Center in downtown and the facility on the southern tip of Terminal Island at the port, remained operational despite the pandemic. Prisoners and deportees were in fact locked down, as always, but they were not even remotely socially distanced from bunk mates, from others in the showers and cafeterias, or from the guards.

My walking became the model for what I wanted students to do in preparation for their final projects. They had lost access to their campus and to its libraries and many had such spotty Internet coverage that they were unable to set up a VPN on their personal devices and get access to UCLA’s databases. The course I taught was a writing seminar, so students were each officially required to write twenty pages of research-based essays. According to my own pre-pandemic standards, the students who had no choice but to write papers based entirely on Google searches, online newspaper articles, and other such sources were not going to excel in this course unless I gave them something else to do. So I added autoethnography to the assignment. Students were to write about a topic that was geographically local to where they were locked down. One student chose her own body in relation to a room within her home as a site for research. In addition to whatever sources they found about this place where history had happened, they needed to go there and to visit it. Just as I had gone to places professors mostly just write, read, and talk about remotely from their campuses, I went to these places and sought direct, personal experiences there. This entailed the practice of slowing down, looking at objects like statues from the front and the back, and sometimes leaning in – or literally zooming in – to touch surfaces at these sites. As students went to do their fieldwork, they experienced serendipities of all sorts. One went to visit the site of a massacre against American Indians, and he found the nearby casino was still open during the middle of the pandemic. Another went to visit the site where thirty-three ill-equipped men from Depression-era relief rolls were ordered to fight a fire and died, and she found a copse of thirty-three trees planted in their memories and still growing. This assignment served as the proof that students remained perfectly capable of pathfinding research in the midst of lockdown.

Sensation: how was the landscape inside your body shaped by teaching remotely?

JH – Sensation

I

“We can look at our own individual bodies as a microcosm for a larger body.”¶¶

Anna Halprin

Within the forced process of introspection during our time in quarantine, we had a shift in perspective that provided a more expansive worldview contributing to a stronger awareness of our interconnectedness. As individuals, we are shaped by internal and external forces, both physical and experiential. Some forces we navigate from our lived experiences while others were inherited genetically from our ancestors. We possess the capacity to be aware of how all these fractured pieces of experience impact our bodies and psyches.

The pandemic was/is a time period when people across the globe are having a fully shared experience. This time has become an opportunity to recognize the collective human body and consciousness. Our actions were, and are, vital to our experience. The way in which we tend to our own bodies, communities, and minds directly impacts the whole. The waves of our movements affect those closest to us in our living spaces and others whom we encounter digitally, and that wave continues out into unknown distances of efficacy. During the initial months of safer-at-home we were in a heightened context of being, unable to be anywhere else but right here, which could be a terrifying realization. I am reminded of the words by transdisciplinary artist SkyE who states, Taking a long hard look at where we are, in this exact moment, we transcend the challenge of judgmental mind and rise to authenticity. We were given a great opportunity to move beyond habits, recognize our interdependence, and embrace “groundlessness.”##

II

“It’s like a boat filled with people crossing the ocean: If they encounter a storm and everyone panics, the boat will capsize. But if there is one person in the boat who can remain calm, that person can inspire other people to be calm. And then there will be hope for the whole boatload.”***

Thich Nhat Hanh

While teaching remotely, I understood that I was responsible for my boatloads of students. As I stayed true to the learning outcomes for each course, I conceived of ways where I could contribute positively to our well-being in a state of emergency. Dance, dialogue, and self-care were on the menu each day during class. The students learned from me and I learned from them. We made connections, felt joy in our bones after hours of dancing, and reamined curious even though students expressed missing being in person. Like the eye in the center of the storm, we danced to make space for our own experience. Witnessing one another, moving wholeheartedly, and feeling at home in our bodies, we shaped these acts of non-corporeal touch and collaboration.

III

“Our bodily wounds eventually close and heal. But there are always hidden wounds those of the heart and if you know how to accept and endure them you will discover the pain and joy which is impossible to express with words. You will reach the realm of poetry which only the body can express.”†††

Kazuo Ohno

Accepting and moving with our wounds is a process of discovering courage. In the spring semester of 2021, as part of the annual CPP Dance Concert I created an interactive performance piece with an ensemble of ten student dance artists presented on Instagram entitled Choice Is... Throughout this entirely asynchronous process; the students responded to a weekly prompt in the form of interdisciplinary art film projects. For the final performance, these cinematic works were accompanied by live presentations via social media where the internet became the stage our feet could no longer tread.

These inspiring responses to prompts around the theme ‘choice’ elicited deep breaths as my ribs widened and contracted. I saw humor, which stretched the corners of my mouth up towards my ears. There was pressure behind my eyes as they welled with tears while witnessing moments of vulnerability. I felt weight like an anchor in my belly after hearing their stories of trauma, struggle, and isolation.

During this process, I had the opportunity to work with four guest artists of various disciplines: dance, music, and performance art. One of these guests was the contemporary artist Yves Gore. Her prompt,

“Choice Is A Wound To Heal [was] another angle [for the students] to access part of themselves. Whether their wounds made them tremble with fear or curiosity, the key thing is they didn’t back off at the face of vulnerability and pain but instead, recognized and embraced these instances confidently, with enough courage to perform what they captured and share with the whole class [and the public], transcending shame and any self-judgement that might have stopped them from doing so.”‡‡‡

In response students were asked to go into their personal history to expose a wound and to use the art making process as an opportunity for healing. Students offered deeply moving stories and found a realm of poetry that was true and potent. I was touched by their willingness and courage to create space to heal through hardship during this challenging time. For the presentation on Instagram, there were over 120 posts equaling three hours of footage created, edited, and choreographed by the student ensemble. It was a ripe time for a process of self-discovery and creative rigor which aimed to encourage a sense of wholeness for each student dance artist.

IV

“Borders (What’s up with that?) Politics (What’s up with that?) Police shots (What’s up with that?) Identities (What’s up with that?) Your privilege (What’s up with that?) Broke people (What’s up with that?) Boat people (What’s up with that?) The realness (What’s up with that?) The new world (What’s up with that?) Am gonna keep up on all that.”§§§

M.I.A

In the wake of large systemic incongruities being revealed on the world stage, myself and two colleagues recorded a multi-location remote conversation discussing the body for my fall 2020 dance history course. Historian Peter Sebastian Chesney, dance colleague Kim Gadlin, and myself had a dialogue about place, identity, and the body. Peter, on zoom, took us to three sites during a historical walking tour. We discussed the body in relation to policing while visiting the Officer Patrick Downey memorial, queer spaces such as Elysian Park, and the shifting infrastructure of the L.A. River. Peter traversed these spaces sharing in-depth historical information and his own connections to these spaces. The borders of our flesh, the nuances of identity, and the heated political climate triggered our bodies, which provoked our mouths into honest conversation. As a result of this dialogue, my students were inspired to share, honestly and openly from their own perspectives. They recorded themselves discussing fear, overwhelm, and inspiration stemming from their gender identities, their experiences with policing, and a desire for a safe space where non-normative people could gather without the fear of persecution or harm.

PSC – Sensation

1/6 was the very first day of my winter quarter sensory history seminar. I was sitting on the concrete at the very edge of the L.A. River when I opened the zoom app and students began entering. For just a few hours, we had all been watching for news from the Capitol: the headlines, the videos, the tweets, and the talking heads. Since we did not yet know how disorganized this attempted coup d’état was, this first hour of conversation was highly speculative and worrying. It was in the context of this heightened anxiety that I proposed a discussion question that I had never used before: where in your body do you experience sensations while you learn about the historical past? This question hit a nerve, and the conversation proceeded for an hour. Students opened up about their emotional states. They talked about how history has sometimes moved them to grow misty eyed, to get a choking sensation in their throats, to become tremendously fatigued, to clench their jaws, to get goosebumps, and to fidget. Finally, one brave and rather brilliant discussant turned the conversation back to me. The students had just disclosed their traumas, their synesthesias, and the various states of their bodies. What about my body? Where did I feel history? I had two answers. At first, I had to learn how to repress such feelings because they had been far too overwhelming when I started graduate school. The awful things I had read about massacres like Gnadenhutten, My Lai, and other such tragedies had made me weep. After a year, I was finally insensitive enough to these accounts that I could read, discuss, and write about them calmly and coolly. The exception was that I sometimes still got a discomfort in my gut. The internal feeling I get when historical awareness overwhelms me can send me running to the bathroom to this day.

The student who asked this wonderful question dropped the course a couple weeks later, so I cannot claim that my method was welcome to all ears. However, another student from this same bunch had this to say in their course evaluation after the whole quarter had passed:

The class has caused me to, quite literally, sense the world around me in new ways. I now ask myself questions about how academic subjects make me feel – what emotions and sensory perceptions they provoke – and have thus come to appreciate the embodied and aesthetic aspects of ‘disembodied’ and abstract fields like math and science.

All I had wanted was to sensitize students in all discourses to their bodies and to the bodies of others. I am convinced that these methods have the potential to humanize technology and the sciences, and my ways of humanizing were specific to remote teaching and these opportunities to bring students on tours of the city via the zoom smartphone app.

However, the power of zoom to humanize is hardly universal. I had a visitor, a dear friend, come to meet with us when I took the students to Watts Towers. For me, bringing students and their gaze through the eye of my smartphone into marginalized spaces has been a worrying enterprise. After all, it was at Watts Towers where I have repeatedly shown students my arm, which features a tattoo copied from this art installation. I got it because the White ethnic immigrant and Pentecostal preacher named Sabato Rodia who made it called it Nuestro Pueblo. This is also the city I study and where I have lived most of my life. For my friend Dr. Marques Vestal, Watts is literally his home where he and other people of color are constantly struggling to survive. So I invited him to take the floor. We rested on a bench together while he explained how to read the area. He had students start with Google maps and the physical infrastructure of the land. Then he transitioned to a tale from his own childhood, a memory of the time a driver’s ice cream truck broke down. He and several other kids looted food from the abandoned vehicle, for the driver had always treated them with cruelty. This lesson was meant to teach my students about how the rules change in the transition from one part of the city to another. They were to unlearn the utmost respect for property most of them had acquired in childhood. Instead, one student blurted out that my guest, a Ph.D. and professor of urbanism, was being “so irresponsible.” The student sneeringly asked, what if someone came and stole the headphones off our heads, and he promptly rage-quit the seminar. Dr. Vestal had a useful, convincing response to this young White man, but the angry student had deployed a power specific to remote learning. It was as easy to turn off a scholar’s voice as it was to turn off any other streaming service. What I found particularly alarming about this encounter was when I asked, at the beginning of the next class, about how last week’s class had ended. Another student, also White, thought she remembered that my guest had stolen someone’s headphones when he was a kid. I had to stop her and disabuse her of her garbled recollection of what had been said. The zoom format endows White rage with an unjust and terrible power to reshape reality.

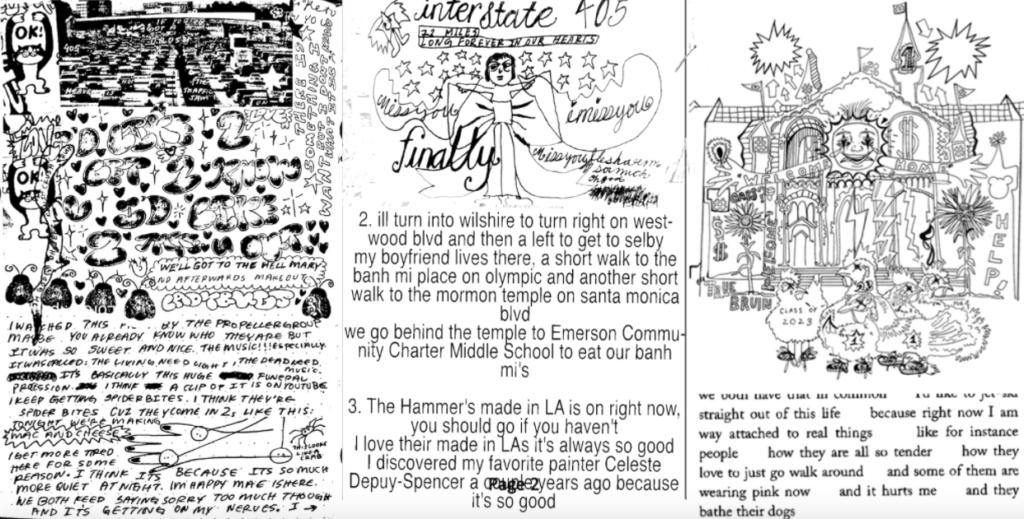

Though I warn of the power of whiteness to structure virtual reality prejudicially against blackness, I can also recount a time of healing through zoom that amounts to the most significant moment in the entire arc of “Touch.” That was when Jeremy came as a guest to the class and led an exercise. The setting was at artist Judy Baca’s Great Wall of Los Angeles in the Valley. My guest asked the students to engage in a number of exercises. They took deep, slow breaths, allowed themselves to meditate in silence, and took some time not to think about any as-yet unfinished tasks. Then he invited us to place our hands on our feet and to trace the topography of our bodies. We touched our shins, our hips, our ribs, our elbows, our necks, and the crowns of our heads. All the while, we reminded ourselves that we have these bodies, which we share in common with all people named in historical textbooks. We realized we too carry histories in these bodies. Historical information was passed from the past into our present through our genetic codes and the ways we have mimicked those who set an example for us. Historical events from earlier in our lives have left marks on our skin and aches in our joints. After Jeremy left and the class ended for the day, I began office hours with one of the students. This had been a difficult quarter for her, and she shared that she had started to sob during Jeremy’s zoom exercise. She felt she had previously not been able to relax all quarter. Furthermore, she was recovering from a recent crash, and his instructions to touch an injured body part had led her to consider the validity of her pain. It was during this conversation that this student pushed past a barrier preventing her from requesting the accommodations she needed to be able to pass this course. Due to her injury, she was on the brink of getting dismissed from the university. She was not going to be able to write a fifteen-page term paper, but we were able to brainstorm a suitable alternative. Her ‘zine got done. She passed. Jeremy’s visit helped make this possible.

PSC – Conclusion

Who are we to speak of the city, of these times, and of the body? Sure, we are children of Los Angeles, but we are children of a specific area (its northern suburbs) and a specific time (the 1980s). Our positionalities constrain our perspectives and leave so much knowledge we want to know outside our frame of reference. That being said, we believe in the value of our dialogue.

Sensory history came to me as a person with a hearing impairment. I have been totally deaf in my left ear since 2008 when I was twenty-two. As my brain kept developing in the years after the bicycling crash that broke my skull, my positionality changed. To pass was easier for me than for many others in the Deaf culture. I held a job for five years and never had to apply for disability benefits. The Ph.D. program at UCLA helped me discard outmoded meritocratic notions that had me quietly convinced students and scholars should be compared objectively. Gone was liberalism’s myth of racial colorblindness. People of color need affirmative action programs to make up for disadvantages born in long histories of structural racism. People with debilities, myself included, deserve recognition for the disadvantages we face in structurally ableist societies. Critical disability theory is the legacy of critical race studies, intersectional feminism, queer theory, and so much other oppositional intellectual work. It is with gratitude to all these scholars and activists that Jeremy and I decided to produce this document.

We recognize the workers who built the devices we used to do our own work, we recognize the stolen land upon which we were able to discuss these ideas, and we recognize the dangers to the future of life on earth presented by our machinery, which requires the use of irreplaceable resources. However, we celebrate what these devices made possible for us as educators with fingers, feet, and feelings internal to our bodies. To a remarkable extent, our pedagogy of embodiment surpassed what might have been had our students been face to face with us. Furthermore, the economic and ecological costs of remote learning are so much less than those of flying students from around the world to UCLA and Cal Poly Pomona and forcing them into Southern California’s housing market.

JH – Conclusion

As a queer artist and educator, I spend time questioning the unfixed essence of my fluid queer identity. Each day becomes a process of embracing liminality and living a life of embodied agency. In queerness, the concept of self is in flux. I acknowledge the relative view seeing me simply as a white, able, male bodied person. In being part of the ever changing, adapting, and evolving LGBTQIA+ community, my essence resides in a unique space that is and is not identifiable. Our presence exists outside of three dimensions into the multidimensional. This is boundlessness. I was given the opportunity to deeply question my existence because of my mystical queer identity. This questioning and living a life as an artist informs my pedagogy. I practice daily on the path of liberation and do my best to create a learning environment where students are encouraged to be uniquely themselves. Working in the field of dance and performance, I use embodiment to encourage vulnerability and the cultivation of presence. Swirling in the flowing drapery of queerness, I engage with life and teaching to transgress the normative into a space beyond, arriving complete and authentic, refining methods for my students to continually decide how they show up in this world, and recognizing how I choose to place each careful foot moving forward.

Acknowledgements

To our students, you’ve given us so much to feel,

and to the software developers at Zoom Video Communications.

Italicized contributions from SkyE

- *~Rheingold, *Virtual Reality: exploring the brave new technologies of artificial intelligence and the interactive world* (1993) as quoted by Michael Bull, “Sensory Media: Virtual Worlds and the Training of Perception,” in *A Cultural History of the Senses in the Modern Age*, Volume 6, David Howes, ed. (Bloomsbury, 2014), 235.

- †~Octavia E. Butler. *Parable of the Sower* (Warner Books, 1995), 1.

- ‡~Jan Cooper. Queering the Contact Zone Author(s): Jan Cooper Source: JAC , 2004, Vol. 24, No. 1 (2004), Published by: JAC

- §~bell hooks, *Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom* (Routledge, 1994), audiobook, 7 hours and 28 minutes.

- ¶~Brian Seibert, “A Home Version of Trisha Brown’s ‘Roof Piece,’ No Roof Required,” *New York Times*, 7 April 2020.

- #~In the USA, the 1930s WPA’s Federal Writers Project began research on this six-volume series, but anti-communist crusaders intervened before it published. A historian has compiled thirty-four of these stories by workers about their jobs and worksites into *Men at Work: Rediscovering Depression-Era Stories from the Federal Writers Project*, Matthew L. Basso, ed. (University of Utah Press, 2012).

- **~Gary Urton, *Inka History in Knots: Reading Khipus as Primary Sources* (University of Texas Press, 2017), x. For the best example of a touchy manifesto, see Donna J. Haraway, *Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene* (Duke University Press, 2016).

- ††~Outside the social sciences, attention to the hands is much more robust. Teachers in physical education, music, the visual arts, and the hard sciences show students at every level how to throw a ball, how to place the pads of fingers on the keys, how to mold clay, and how to harvest nematodes. For more on this matter, see Steven Mintz, *Huck’s Raft: A History of American Childhood* (Harvard University Press, 2004), 174-175.

- ‡‡~Thich Nhat Hanh. *I Have Arrived, I Am Home* (Parallax Press, 2003).

- §§~Isadora Duncan, “The Dancer of the Future” in *The Art of the Dance* (Theatre Arts Books, 1928 [originally 1902]).

- ¶¶~Abrahams, Andrew, dir. *Returning Home*. Open Eye Pictures, 2003.

- ##~Pema Chödrön, “The Fundamental Ambiguity of Being Human,” *Tricycle: The Buddhist Review,* fall 2020, https://tricycle.org/magazine/fundamental-ambiguity-being-human/

- ***~Thich Nhat Hanh, “Fearlessness and Togetherness: Q&A with Thich Nhat Hanh,” *The Mindfulness Bell,* January 26, 2021, https://thichnhathanhfoundation.org/blog/2021/1/26/fearlessness-and-togetherness-qampa-with-thich-nhat-hanh

- †††~Sondra Fraleigh. *Butoh: Metamorphic Dance and Global Alchemy* (University of Illinois Press, 2010), p172.

- ‡‡‡~Yves Gore, email message to Jeremy Hahn, July 29, 2021.

- §§§~M.I.A., “Boarders,” track 1 on *AIM (Deluxe),* Interscope Records, 2016, MP3.