Jean Baudrillard predicted our present in Simulacra and Simulation when he argued that our reliance on maps and models has preceded our connection to the real world: “The territory no longer precedes the map, nor does it survive it. It is nevertheless the map that precedes the territory—precession of simulacra—that engenders the territory”.* Our society has surpassed the modern and entered the postmodern (or metamodern) where screens dominate the way we experience our surroundings. We have learned to read what is on our screen as a [an accurate] simulation of what exists in reality. According to Baudrillard, when it comes to postmodern simulation and simulacra, “it is no longer a question of imitation, nor duplication, nor even parody. It is a question of substituting the signs of the real for the real”.†

When street art enters the internet, it, too, is displaced from its materiality (the urban environment) and re-placed into a digitality, becoming a simulacrum of itself. Like any other object inserted in the digital context, street art’s simulacra is realized as photography. Here, photography possesses an expansive definition that includes any visual form using the pixel as its base unit: videos, digital illustrations, animations, as well as the photographic image. Digital street art exploits the pixel’s malleability to easily adapt to a hyperflat surface—the screen—and its disposition to permeate numerous screens and hard drives to capture the attention of the online audience.

Street art’s ephemerality—it is often buffed (chemically removed) or painted over—is hyperinflated when viewed on the internet because its photographic replica is no longer rooted in physical time and place, yet, it exists on multiple screens and is immortalized on infinite cloud drives. Because of this, digital street art can express multiple forms and possibilities that is realized through its use of the pixel as its primary unit and cannot necessarily be realized as a physical piece. This multiplicity ascribes digital street art as super-ephemeral because it straddles the line between form and formless, real and not real, possible and impossible—similar to visual artist Takashi Murakami’s description of postmodern Japanese visual culture as superflat. First coined by Murakami, superflat describes various flattened forms in contemporary Japanese visual culture that rose out of otaku subculture, a group of enthusiastic consumers of Japanese post-war phenomena and popular cultures generally associated with computers, such as manga, anime, gaming and computer hacking.

Otaku culture is, according to Marc Steinberg, a product of American influence on postwar Japan just as much as it is a quintessentially “Japanese” symbol of contemporary Japanese identity. Formed by a historical idealization of the Edo period, well-known for woodblock prints, geishas and kabuki, otakus praised it as a time of an idyllic, pre-Americanized Japan and hyperinflated its visual culture by recontextualizing it within a post-WWII, American-occupied Japanese society. This created a new visual culture that is often linked to a grotesque sexuality generated by isolating desired elements of an image or images and synthesizing the elements into a new image that could only be a result of otaku imagination and computer literacy. This method of image-making also influenced a new generation of Japanese visual artists who heavily incorporate mass consumer culture in an assemblage-like manner in their work. These artists, such as Takashi Murakami, Yoshitomo Nara, Aya Takano and Chiho Aoshima, were part of visual artist and curator Takashi Murakami’s seminal show Superflat, which validated the movement (and terminology) and otaku culture. Though these artists work in various media (painting, sculpture, hand-drawn and digital illustrations, among others), their works display a certain type of flatness and mobility of gaze that Murakami called “superflat” and credited to the influence of Edo-period painters, such as Kano Sansetsu and Katsushika Hokusai. Steinberg concludes that this new visuality is “a continuing resistance to the semiotic constellation of [Western] modernity, with its emphasis on depth and interiority, and the subterranean persistence of a premodern semiotic emphasizing surface and word-play from Japan’s nineteenth century onwards (a semiotic that once again surfaces in Japan’s postmodern present).”‡

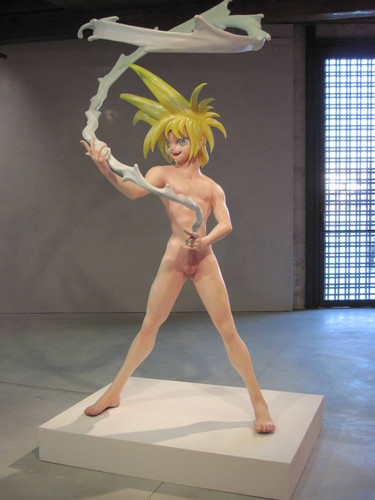

Murakami’s My Lonesome Cowboy (Figure 1) is one such example of the grotesque visuality that is popular among otakus. The sculpture is of a stereotypical anime male figure who is naked, has spiky blonde hair and large blue-green eyes, and is holding his erect, unproportionately large penis with his left hand while he ejaculates a trail of cum that swirls into the air above him. His gesture shows him holding his penis-cum trail like a rope lasso that could also double as a weapon. This uninhibited, ludicrous sexuality is pure fantasy and reflects an unrealistic visuality that otakus desire. Cultural theorist Hiroki Azuma connects otaku visual culture to the vision of the database eye (versus the camera eye), in which images can be stored, found, picked apart for desirable elements and recontextualized into a new image, accounting for the viewer’s own part in the simultaneous consumption-production of the artificially synthesized image.§ My Lonesome Cowboy shows several unrealistic elements (cum lasso, non-realistic representation of the male form, etc) being combined together through the eyes of an otaku participant—in this case, the artist himself, who has openly claimed to being influenced by the subculture—to create a figure that could only exist in the imaginary world of anime. Azuma claims that Murakami’s visual art “represents the postmodern bilateral structure visually covered with many multiplying holes to the database after the modern absolute perspective is lost. Confronted with anime or game imagery, we are not stared back at by the author’s gaze but by an anonymous database. The super of superflat is the database, and the flat is the simulacra.”¶ Superflat is no longer concerned with dimensionality, despite Murakami’s sculpture being a constructed form, but rather, with a visual epistemology in the postmodern era: the recontextualization of the physical object in digital space and its resulting “superflatness”, formlessness or potentiality of limitless orientations. The digital object becomes a semiotic of its physical self, or a simulacrum, exhibiting signs of its physical object in its photography without ever actually possessing any of its physical attributes. It is a digital image, after all.

The hyperflatness of the screen and (theoretically) unlimited access to information on the internet has paved the way for new digital techniques and formats to be adapted to street art as well. GIFs (Graphics Interchange Formats), animations, photomontages, applications and websites are now fair game for street artists to explore and manipulate. This new way of seeing has prompted street artists to create art that is both made to be seen online and to be a semiotic of itself as street art in digital space—or that is super-ephemeral. The lack of a spatiotemporal context in digital street art has forced artists to find a new context in which they can produce their digital works. This new context is the internet and social media and it has influenced the aesthetics of street art to reflect a new contemporary identity that is self-referential.

One example of super-ephemeral street art is Insa’s GIF-iti. INSA is a London-based artist who purposefully uses street art to create GIFS (or what he calls “GIF-iti”). He paints a mural and takes a photograph, then he paints over the first mural with a new mural that deviates slightly from the first and takes a photograph of the new mural, and he continues this process until he has enough frames to loop into a short GIF that can be widely disseminated to an online audience. INSA’s GIF-iti is animated—light up, move, change shape—while staying in place on a wall, and they do not require a time and place for people to experience because it is made to be viewed online, anytime and anywhere. As a GIF, INSA’s murals become digital objects (Figure 2). According to a street art outdoor gallery project, Unit44’s White Walls Project, who has worked with Insa, his GIF-iti “exaggerates the ephemeral nature of graffiti as each layer is painted instantly over the last. Mixing retro internet technology and labour intensive painting, INSA creates slices of infinite un-reality, cutting edge art for the Tumblr generation.”# Though the artist is using the analog technique of mural painting to create his GIF, his piece is incomplete as a mural; his individual paintings are only part of the piece and the final work is not completed until it reaches its programmed consciousness as GIF-iti. The “infinite un-reality” refers to GIF-iti’s ability to create an alternative realm where street art constantly manipulates the built environment—a street artist’s utopia. Digital street art is not about marking the physical space, but rather, about making the artist’s utopia a potential reality.

Today, the signs of the real are the real. The superflatness of the internet has shaped a new epistemology of understanding our postmodern society. Images, maps and data have permanently altered the way we connect with our physical world and have also made us hyperaware of the omnipresence of digital technology and the internet. Street art, too, has also adapted to this epistemology through its adoption of digital software, photography, and a new visual language understood through our connection to the digital. This visual language represents itself as no longer associated with physical geography but rather, with digital space. With the pixel as a universal unit of measure in the online world, we are experiencing a quasi-renaissance of photography. Social media, host sites and other online platforms are moving more towards an image-based format; thus, it makes sense that street artists would take advantage of the photograph’s potentiality to disrupt screens and cybernetic space, and disseminate their art to a worldwide audience in mere seconds. Digital street art is no longer street art, rather, it is super-ephemeral.

- *Jean Baudrillard, _Simulacra And Simulation_, (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994), 1.

- †ibid, 2.

- ‡Marc Steinberg, “Otaku consumption, superflat art and the return to Edo,” _Japan Forum_, October 2004: 459.

- §Hiroki Azuma, “Superflat Japanese postmodernity” (lecture, Pacific Design Center, April 5 2001), https://www.scribd.com/document/99174676/Azuma-Hiroki-Superflat.

- ¶ibid.

- #RJ Rushmore, _Viral Art_ (Pressbooks.com, 2013), 227.